Code

library(rms)

library(ggplot2)

library(splines)

library(lspline)

library(lmtest)

library(sandwich)

library(car)

library(knitr)

tryCatch(source('pander_registry.R'), error = function(e) invisible(e))Lecture 11

October 30, 2025

library(rms)

library(ggplot2)

library(splines)

library(lspline)

library(lmtest)

library(sandwich)

library(car)

library(knitr)

tryCatch(source('pander_registry.R'), error = function(e) invisible(e))When covariates are measured on a continuous scale, we have many different approaches to analysis

To date, we have focused primarily on approaches that facilitate interpretation of our parameter estimates

Flexible modeling of continuous covariates are another option

Interpretation often relies on plots, except in special cases

It is best to pre-specify how we intend to model continuous covariates to avoid data-driven modeling decision

We have many choices for modeling dose-response

Consider the scientific question when deciding on an appropriate model

How does the scientific question you want to answer relate to how you model the dose-response relationship?

Will describe methods for

Modeling complex dose-response curves

Flexible methods (non-parametric loess smooths, parameteric regression splines)

When testing for associations, we are implicitly comparing two models

“Full” model

Usually corresponds to alternative hypothesis

Contains all terms in the “restricted” model plus some terms that we want to test for inclusion

Example: \(g(\theta) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * X_1 + \beta_2 * X_2\)

“Restricted” model

Usually corresponds to the null hypothesis

Terms in the model are the subset of the terms in the full model that are not being tested

Example: \(g(\theta) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * X_1\)

Jargon: The restricted model is “nested” in the full model

If we set some parameters in the full model equal to zero, we will get the restricted model

We have very good methods for testing differences between nested models

Our methods are not as good for comparing models that are not nested

Non-nested models (e.g. \(X_1\) is weight, \(X_2\) is height)

\(g(\theta) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * X_1\)

\(g(\theta) = \gamma_0 + \gamma_2 * X_2\)

Our scientific interpretation of our statistical tests depends on the meaning of the restricted model compared to the full model

Appears very straightforward when we are only considering one full model compared to one restricted model

In practice, we may have many restricted models in mind

Multiple testing problem appears if we are considering many restricted models

Full model: FEV vs smoking, age, height

Restricted model: FEV vs age, height

If the full model provides no clear advantage over the restricted model, then we conclude that there is insufficient evidence to suggest an association between FEV and smoking when controlling for age and height

Note how carefully I stated the above

“Insufficient evidence” (not evidence that smoking is not associated)

Conditional on controlling for age and height. Smoking, alone, may be an important predictor of FEV. The question answered by the full and reduced model is a comparison of FEV “among individuals of the same age and height but differing in smoking status” not just individuals who differ in smoking status.

Full model: Survival vs cholesterol and cholesterol\(^2\)

Linear and quadratic terms for cholesterol

Model allows for a parabolic shape for chelesterol

Restricted model: Survival vs cholesterol

If the full model provides no clear advantage over the restricted model, we conclude that there is insufficient evidence to suggest a U-shaped trend in survival with cholesterol

Note that a quadratic term does not include all possibilities for non-linearity. We will cover other (better) approaches later in the notes

Wald test

Fits only the full model

Tests if the parameter (or parameters) in the full model are equal to zero

Can be used for robust and non-robust standard error estimates (fit using GEE)

Likelihood Ratio test

Fits both the full and reduced model

Compares the likelihood functions to determine if they are significantly different

Can be used for non-robust models only (fit using likelihood)

Score test

Only fits the reduced model

Considers the gradient of the likelihood function. After fitting the reduced model, looks at what is left over to see if it can be predicted by additional covariates

Not generally reported in regression model setting, but some common tests are Score tests (e.g. log-rank test)

In large samples, the Wald, Likelihood Ratio, and Score tests converge

Models to test for effect modification (interactions) are hierarchical

Full Model: Include the interactions

Reduced Model: Set the interactions to be tested in the full model to zero

Best scientific approach is to pre-specify the statistical model that will be used for analysis

Sometimes we choose a relatively large model including interactions

Allows us to address more questions (e.g. effect modification)

Sometimes gives greater precision

Deciding which parameters to test from the full model

It can be difficult to decide the statistical test that corresponds to specific scientific questions

Need to consider the restricted model that corresponds to your null hypothesis

In the following examples, the full model is the same but we change the restricted model based on the scientific question

Full model: Survival vs sex, smoking, sex-smoking interaction

Example Question 1: Is there effect modification?

Restricted model: Survival vs sex and smoking

Example question 2: Is there an association between survival and sex?

Restricted model: Survival vs smoking

Test that parameters for sex and sex-smoking interaction are zero

Does sex effect survival in either smokers or non-smokers?

Example question 3: Is there an association between survival and smoking?

Restricted model: Survival vs sex

We are often tempted to remove parameters that are not statistically significant before proceeding to other tests

You will find many textbooks that advocate using this analysis approach

e.g. fit the interaction, if it is not significant, exclude it from the model

Such texts are invariable written by mathematicians with no understanding of the underlying science

When you work in the same scientific area, you will eventually “discover” false-positive assocations if you use this model building technique

Such data-driven analyses tend to suggest that failure to reject the null means equivalence

But, if you make this conclusion, you are wrong (large p-values do not indicate equivalence)

Abscence of evidence is not evidence of abscence

A procedure where we fit one model, and then use the results to determine the next model we will fit tends to underestimate the true standard error

A consequence of the genearl multiple testing problem

Will lead to declaring statistical significance more often than you should (inflates type-I error rate)

May also lead to parameter estimates that are biased away from the null

Statistical significance increases as a function of the effect size and the inverse of the standard error

If, by chance, you see a large effect in your sample, you will be more likely to declare significance

How we interpret “negative” studies

There are other many reasons for not rejecting the null hypothesis of zero slope

There may be no association

There may be an association, but not in the parameter considered (i.e. the mean response)

There may be an association in the parameter considered, but the best fitting line has zero slope (a curvilinear association in the parameter)

There may be a first order trend in the parameter, but we lack sufficient statistical precision to be confident that it truly exists (a type-II error)

Be careful to not just assume that it the first reason, no association

Statistically, there is no way of discriminating between these four possibilities unless you have an infinite sample size

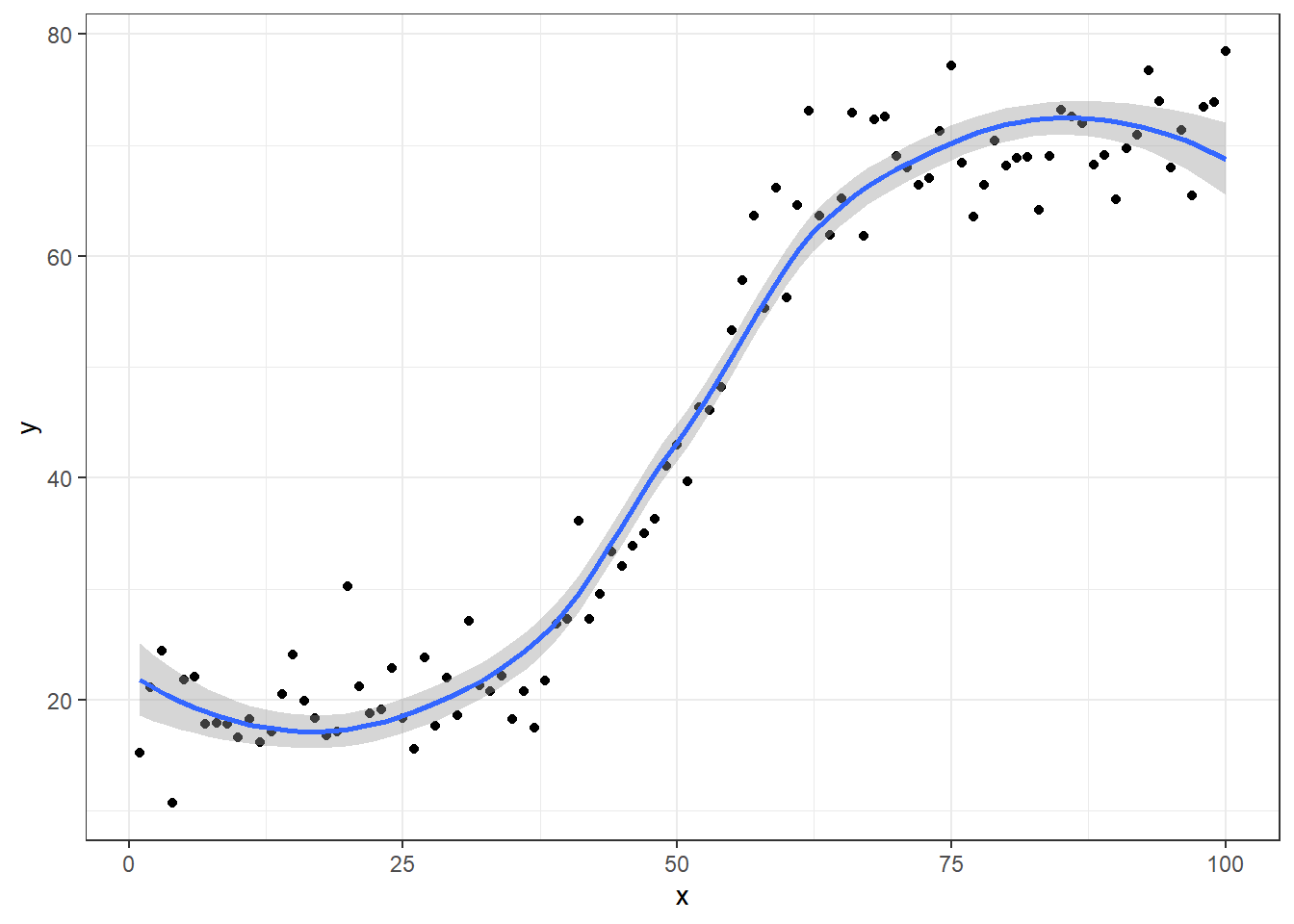

set.seed(1234)

n <- 100

plotdata <- data.frame(x=1:n,

y=20 + 50 / (1+exp(-.15*(1:n-50))))

plotdata$y <- plotdata$y + rnorm(n,0,4)

ggplot(plotdata, aes(x=x, y=y)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() + geom_smooth()

If we happen to sample over the entire range of \(X\) (in this example, from 0 to 100), we will would observe all parts of the S-curve

However, if we were only to sample from a limited range of \(X\), we might observe only parts of the curve where it was approximately linear

plotdata$xint <- cut(plotdata$x, c(0,30,70,100))

ggplot(plotdata, aes(x=x, y=y)) + facet_wrap(~ xint) + geom_point() + theme_bw() + geom_smooth()

The default smooth for ‘geom_smooth’ when there are fewer than 1000 data points is a loess smooth. These fits appear in the plots above

Loess is a non-parametric smooth where fitting is done locally.

That is, for the fit at point x, the fit is made using points in a neighborhood of x, weighted by their distance from x

There are arguments to control the degree of smoothing, or how close we consider points to be in the “neighborhood of x”

‘loess’ provides a nice visual representation to variety of data without having to specify a model

We will primarily be concerned with parametric smoothers as the parameters can be estimated (and in special cases interpreted) from multivariable regression models

The most commonly-used regression models all consider “linear predictors”

Linear refers to linear in the parameters (\(\beta\)s), and is not a reference to transformations of the predictors

The modeled predictors can be transformations of the scientific measurements and still be linear (in the parameters). These models are linear (in the parameters)

\(g[\theta | X_i] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \textrm{log}(X_i)\)

\(g[\theta | X_i] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i + \beta_2 X_i^2\)

Examples of models that are not linear in the parameters (We do not consider such models)

\(g[\theta | X_i] = \beta_0 X_i^{\beta_1}\)

\(g[\theta | X_i] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \textrm{exp}(-\beta_2 X_i)\)

\(g[\theta | X_i] = \frac{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i}{1 + \beta_2 X_i}\)

We transform predictors to provide more flexible description of complex associations between the response and some scientific measure

Threshold effects

Exponentially increasing effects

U-shaped functions

S-shaped functions

etc.

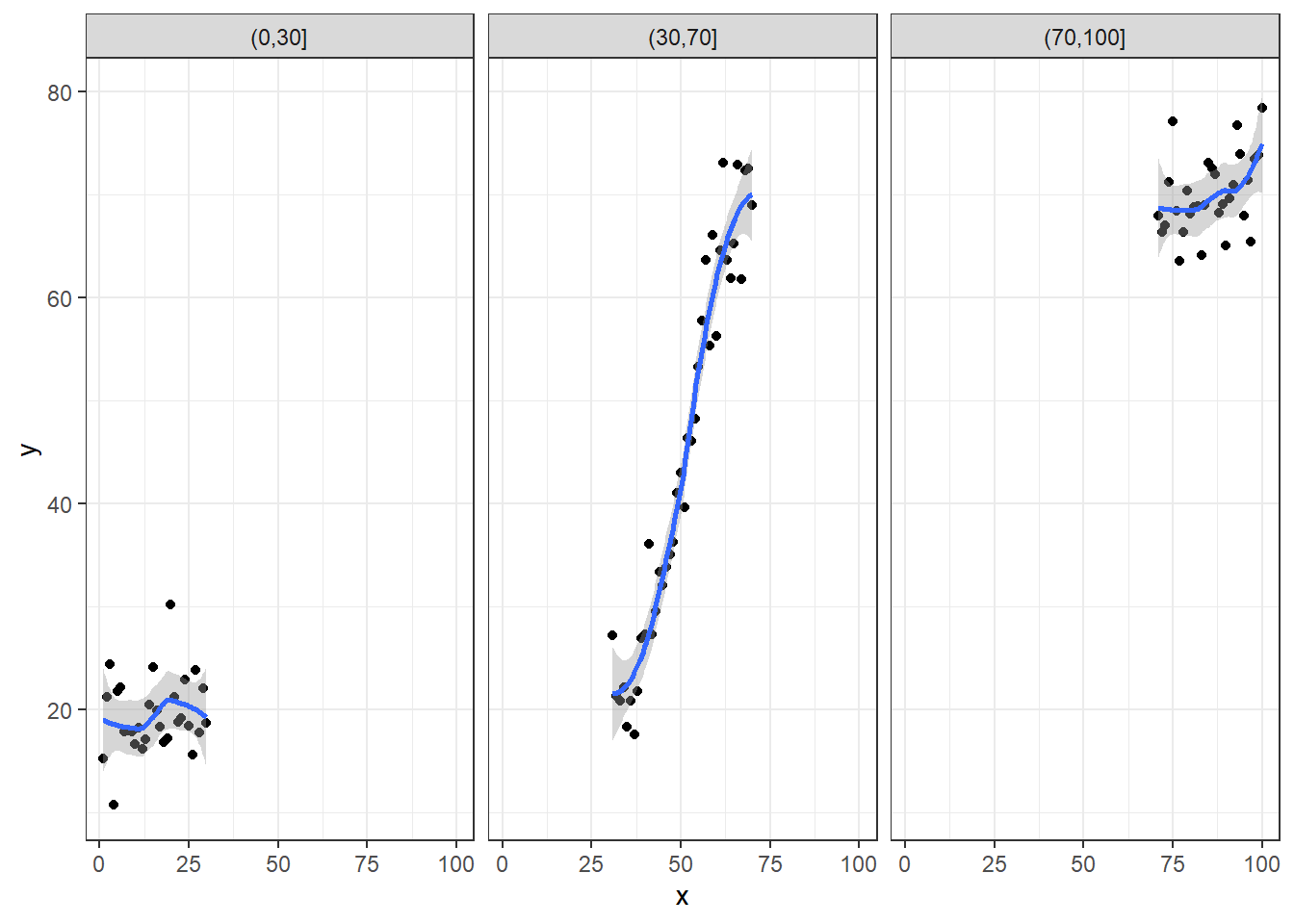

Flexible modeling of continuous predictors was briefly covered in the notes on Poisson regression. We used a flexible dose-response model to examine the association between BMI and reflux rate by Esophagitis status

bmi.data <- read.csv("data/bmi.csv", header=TRUE)

# Events are pH less than 4

bmi.data$events <- bmi.data$totalmins4

m.spline2.adj <- glm(events ~ ns(bmi,4) + offset(log(totalmins)) + esop, data=bmi.data, family="poisson")

m.spline3.adj <- lm(events / totalmins ~ ns(bmi,4) + esop, data=bmi.data)

par(mfrow=c(1,2), mar=c(5,4,4,0.5))

plot(18:40, exp(predict(m.spline2.adj, newdata=data.frame(bmi=18:40, totalmins=720, esop=1), type="link")), type='l', ylab="Predicted number of events per day", xlab="BMI", ylim=c(0,100), main="Poisson Reg")

axis(4, labels=FALSE, ticks=TRUE)

legend("bottomright", c("Esophagitis Pos","Esophagitis Neg"), inset=0.05, col=1, lty=1:2)

lines(18:40, exp(predict(m.spline2.adj, newdata=data.frame(bmi=18:40, totalmins=720, esop=0), type="link")), lty=2)

plot(18:40, 720*predict(m.spline3.adj, newdata=data.frame(bmi=18:40, esop=1), type="response"), type='l', col='Blue', ylab="", xlab="BMI", ylim=c(0,100), main="Linear Reg", axes=FALSE)

axis(1)

axis(4)

axis(2, labels=FALSE, ticks=TRUE)

box()

lines(18:40, 720*predict(m.spline3.adj, newdata=data.frame(bmi=18:40, esop=0), type="response"), type='l', col='Blue', lty=2)

legend("bottomright", c("Esophagitis Pos","Esophagitis Neg"), inset=0.05, col="Blue", lty=1:2)

1:1 Transformations

Sometimes we can transform 1 scientific measurement into 1 modeled predictor and acheve approximate linearity

Ex: log transformations will sometimes address apparent threshold effects

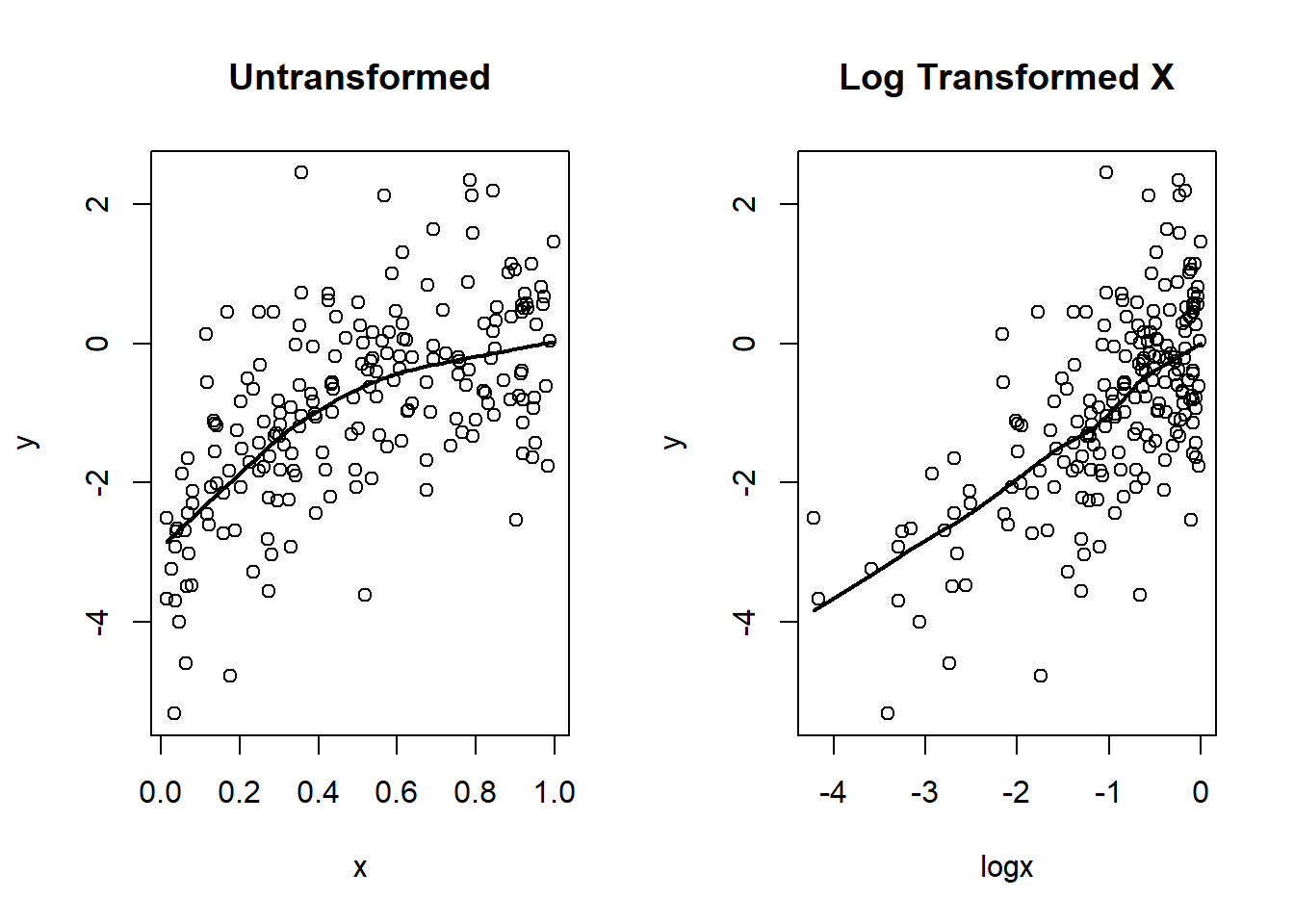

set.seed(33)

n <- 200

x <- runif(n)

logx <- log(x)

y <- 0 + logx + rnorm(n)

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

plot(x,y, main="Untransformed")

lines(lowess(y~x), lwd=2)

plot(logx, y, main="Log Transformed X")

lines(lowess(y ~ logx), lwd=2)

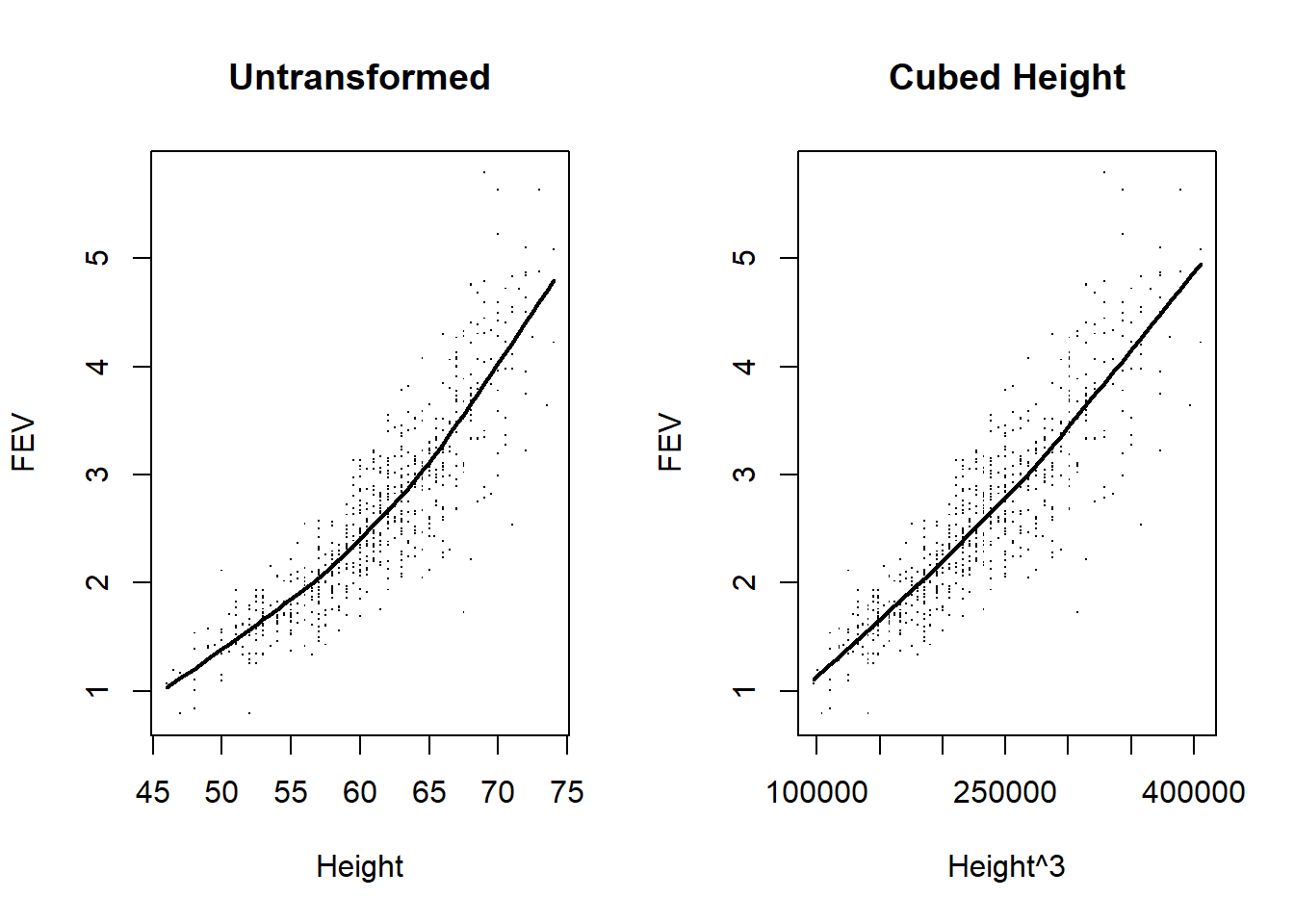

fev <- read.csv(file="data/FEV.csv")

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

plot(fev$height, fev$fev, main="Untransformed", pch='.', xlab="Height",ylab="FEV")

lines(lowess(fev$fev ~ fev$height), lwd=2)

fev$height3 <- fev$height^3

plot(fev$height3, fev$fev, main="Cubed Height", pch='.', xlab="Height^3",ylab="FEV")

lines(lowess(fev$fev ~ fev$height3), lwd=2)

1:Many transformations

Sometimes we transform 1 scientific measurement into several modeled predictors

Polynomial regression

Dummy variables (factor or class variables)

Piecewise linear

Splines

Polynomial regression

Fit linear term plus higher order terms (squared, cubic, …)

Can fit an arbitrarily-complex function

Generally, very difficult to interpret parameters

Special uses

2nd order (quadratic) model to look for U-shaped trends (e.g. alcohol consumption and cardiovascular risk? Potential hypothesis being that moderate consumption of alcohol beneficial relative to either no consumption or high consumption)

Tests for linearity achieved by testing that all higher order terms have parameters equal to zero (hierarchical model)

Full Model: \(g(\theta) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * X + \beta_2 * X^2 + \beta_3 * X^3\)

Reduced Model: \(g(\theta) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * X\)

We can try to assess whether any association between mean FEV and height follows a straight line association

Fit a third order (cubic) polynomial due to the known scientific relationship between volume and height (using robust standard error estimates)

# Create squared and cubic terms

fev$ht2 <- fev$height^2

fev$ht3 <- fev$height^3

m1 <- lm(fev ~ height + ht2 + ht3, data=fev)

coeftest(m1, vcov=sandwich)| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 4.5691e-01 | 1.2339e+01 | 0.037030 | 0.97047 |

| height | 3.0595e-02 | 6.3266e-01 | 0.048359 | 0.96144 |

| ht2 | -1.5222e-03 | 1.0746e-02 | -0.141648 | 0.88740 |

| ht3 | 2.5797e-05 | 6.0481e-05 | 0.426524 | 0.66987 |

From the model output, is height a significant predictor of FEV?

Note that the p-values for each term are not significant

But each of these tests are addressing irrelevant questions

height: After adjusting for the 2nd and 3rd order terms relationships, is the linear term important?

htsqr: After adjusting for the linear and 3rd order terms relationships, is the quadratic term important?

htcub: After adjusting for the linear and 2nd order terms relationships, is the cubic term important?

We need to test if test the 2nd and 3rd order terms simultaneously

linearHypothesis(m1, c("ht2",

"ht3"),

vcov=sandwich(m1))| Res.Df | Df | F | Pr(>F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 652 | |||

| 650 | 2 | 30.641 | 0 |

We find clear evidence that the trend in mean FEV versus height is non-linear (\(p < 0.001\))

Note that if we had seen \(p > 0.05\), we could not be sure it was linear. The relationship may have been non-linear, but not in a way the cubic polynomial could detect

We can try to assess whether any association between mean log FEV and height follows a straight line relationship

Again, we will fit a third order (cubic) polynomial, but this time we do not have any good scientific justification for such a model

fev$logfev <- log(fev$fev)

m2 <- lm(logfev ~ height + ht2 + ht3, data=fev)

coeftest(m2, vcov=sandwich)| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -2.7918e+00 | 4.9700e+00 | -0.561739 | 0.57449 |

| height | 7.0664e-02 | 2.4759e-01 | 0.285404 | 0.77543 |

| ht2 | -1.8281e-04 | 4.0899e-03 | -0.044697 | 0.96436 |

| ht3 | 3.2400e-07 | 2.2404e-05 | 0.014461 | 0.98847 |

Note that again, the p-values for the individual terms are not significant and are still addressing uninteresting scientific questions

Test the squared and cubed terms simultaneously

linearHypothesis(m2, c("ht2",

"ht3"),

vcov=sandwich(m2))| Res.Df | Df | F | Pr(>F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 652 | |||

| 650 | 2 | 0.29449 | 0.74501 |

We do not find clear evidence that the trend in mean log FEV versus height is non-linear

This does not prove linearity because it could have been nonlinear in a way that a cubic polynomial could not detect

However, my guess it the cubic polynomial would have picked up most reasonable patterns of non-linearity likely to occur in this setting

We have not addressed the question of whether log FEV is associated with height

This question could have been addressed in the cubic model by

Testing all three height-derived variable simultaneously

OR looking at the overall F-test (because only height variables are in the model)

Another alternative would be to fit a model with only the linear term for height

In general, it is a very bad idea to go fishing for models, so pick an approach beforehand and use that

If I suspected a complex dose-response relationship beforehand, I would fit the complex model and test all of the height coefficients

If I just cared about showing a first order trend, the following output would answer that question

m3 <- lm(logfev ~ height, data=fev)

coeftest(m3, vcov=sandwich)| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -2.271312 | 0.068447 | -33.184 | 0 |

| height | 0.052119 | 0.001121 | 46.494 | 0 |

Indicator variables for all but one group

This is the only appropriate method for modeling modeling nominal (unordered) categorical variables

Example: Marital status using indicator for

Married (married=1, everything else=0)

Widowed (widowed=1, everything else=0)

Divorced (divorced=1, everything else=0)

Single would then be the intercept

While it is the only approach for nominal variables, dummy variable coding is often used for other settings

Makes regression equivalent to Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

ANOVA is an old technique developed by R.A. Fisher in 1921

Can reproduce results of ANOVA exactly with regression, so ANOVA is of limited use today (but will find it around)

Field is a nominal variable, so we must use dummy variables

salary <- read.csv("data/salary.csv")

salary <- salary[salary$year==95,]

salary$field <- factor(salary$field)

salary$field <- relevel(salary$field, ref="Other")

m4 <- lm(salary ~ field, data=salary)

coeftest(m4, vcov=sandwich)| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 6291.6 | 61.01 | 103.1252 | 0 |

| fieldArts | -1013.6 | 104.73 | -9.6775 | 0 |

| fieldProf | 1225.0 | 133.56 | 9.1718 | 0 |

coefci(m4, vcov=sandwich)| 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 6171.97 | 6411.31 |

| fieldArts | -1218.99 | -808.13 |

| fieldProf | 963.05 | 1487.01 |

Interpretation based on coding used

Intercept corresponds to the mean salary in the Other field

These faculty will have both arts==0 and prof==0

Estimated mean salary of $6292 per month (95% CI: [6172, 6411])

Highly statistically different from $0 per month (a worthless test)

Slope for arts is difference in mean salary between Fine Arts and Other fields

Fine Arts faculty will have arts==1 and prof==0; Other faculty will have arts==0 and prof==0

Estimated difference in mean salary is $1014 lower (95% CI: [808, 1219] lower salary)

Highly statistically different from $0 per month (a useful test, if we specified it a priori)

Slope for prof is difference in mean salary between Professional and Other fields

Professional faculty will have arts==0 and prof==1; Other faculty will have arts==0 and prof==0

Estimated difference in mean salary is $1225 higher (95% CI: [963, 1487] higher salary)

Highly statistically different from $0 per month (a useful test, if we specified it a priori)

Because we modeled the three groups with two predictors plus an intercept, the estimates agree exactly with the sample means

No borrowing of information across field

If we had used a different reference group rather than Other, would also see agreement between model estimates and sample means

Hypothesis test: To test for mean salary differences by field

We have modeled field using two variables

Both slopes would have to be zero for there to be no association between field and mean salary

Want to simultaneously tests the two slopes

linearHypothesis(m4, c("fieldArts","fieldProf"),

vcov=sandwich(m4))| Res.Df | Df | F | Pr(>F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1596 | |||

| 1594 | 2 | 121.08 | 0 |

We can also use dummy variables to represent continuous variables

Continuous variables measured at discrete levels (e.g. dose in an interventional experiment)

Continuous variables divided into categories (often a bad idea)

Dummy variables will fit groups exactly

With continuous variables, dummy variable coding assumes a step-function is true

Modeling with dummy variables ignores order of predictor of interest

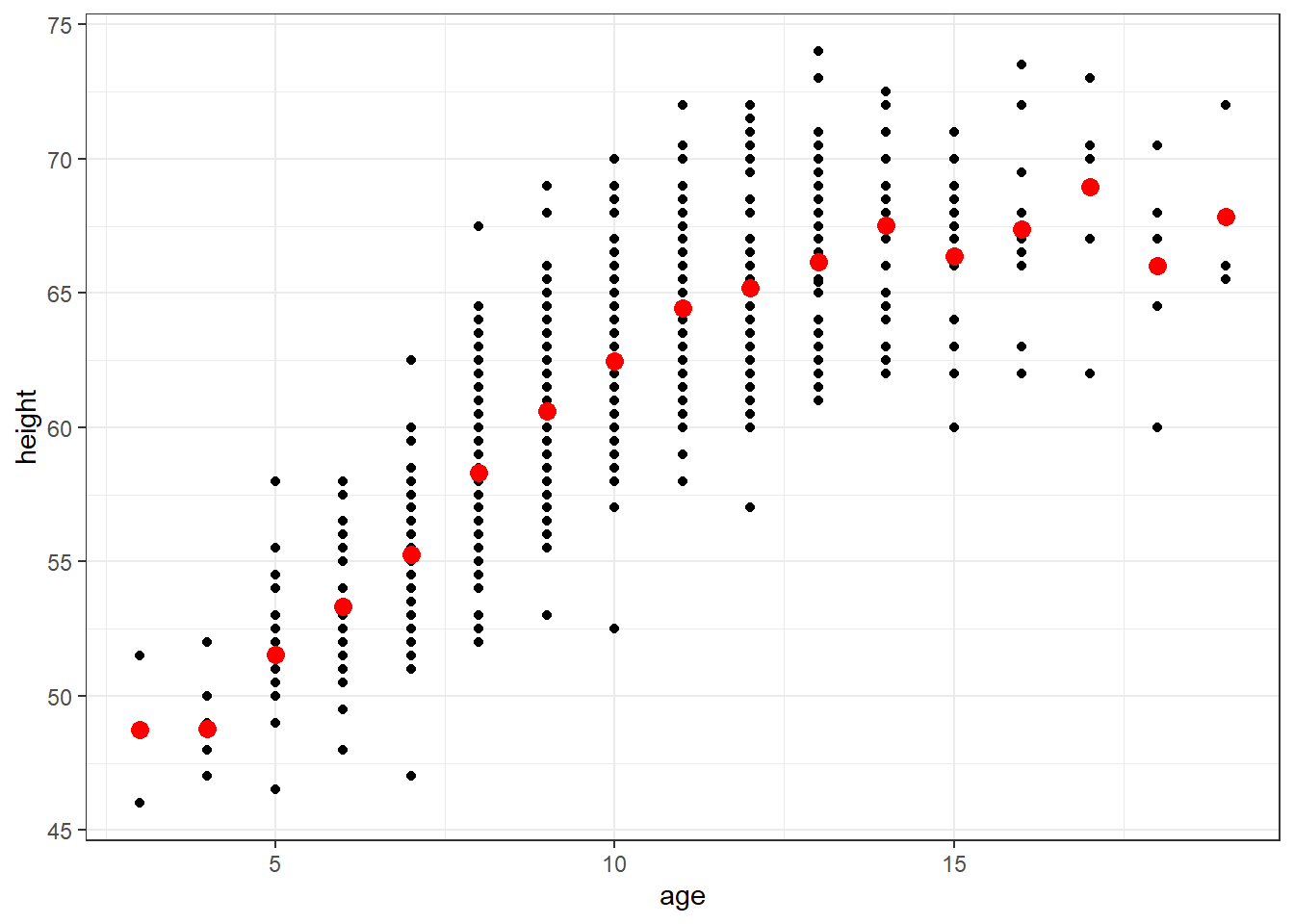

m.dummy <- lm(height ~ factor(age), data=fev)

newdata <- data.frame(age=3:19)

newdata$ht.dummy <- predict(m.dummy, newdata=newdata)

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3)

The red points in the plot represents the mean height by subgroups defined by years of age

Dummy variables are used for each age (measured in years)

Step function (e.g. when age changes from 8.999 to 9.000, expected height increases)

Several ages have few subjects, which makes the estimates unreliable

Do we really believe that average height of 18 year olds is less than the average height of 14, 15, 16, 17, and 19 year old?

Predicted heights for observed ages from the dummy variable and two polynomial models

newdata[12:17,]| age | ht.dummy | |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 14 | 67.520 |

| 13 | 15 | 66.368 |

| 14 | 16 | 67.385 |

| 15 | 17 | 68.938 |

| 16 | 18 | 66.000 |

| 17 | 19 | 67.833 |

We have methods that can fit a wide variety of curve shapes

Dummy variables: Step function with tiny steps

Polynomials: If high degree, allows many patterns of curvature

Splines: Piecewise linear or piecewise polynomial

We can fit high order polynomials to flexibly model a continuous covariate

A continuous covariate with \(k\) levels can be perfectly modeled using polynomials up to degree \(k-1\).

In the Height and Age dataset, there are 17 unique values of age (age is rounded to the nearest year), so we can perfectly model the means using polynomials up to degree 16

\(E[Height | Age = a] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * a + \beta_2 * a^2 + \ldots + \beta_{16} * a^{16}\)

Each \(\beta\) is difficult to interpret, but the predicted value at the integer levels of age make sense.

Predicted values of height at non-integer values of age (e.g. age of 18.5) may not make sense

Polynomials become especially unstable near the upper and lower bounds of the age distribution. Stability near the upper and lower bounds is a general concern in many spline approaches.

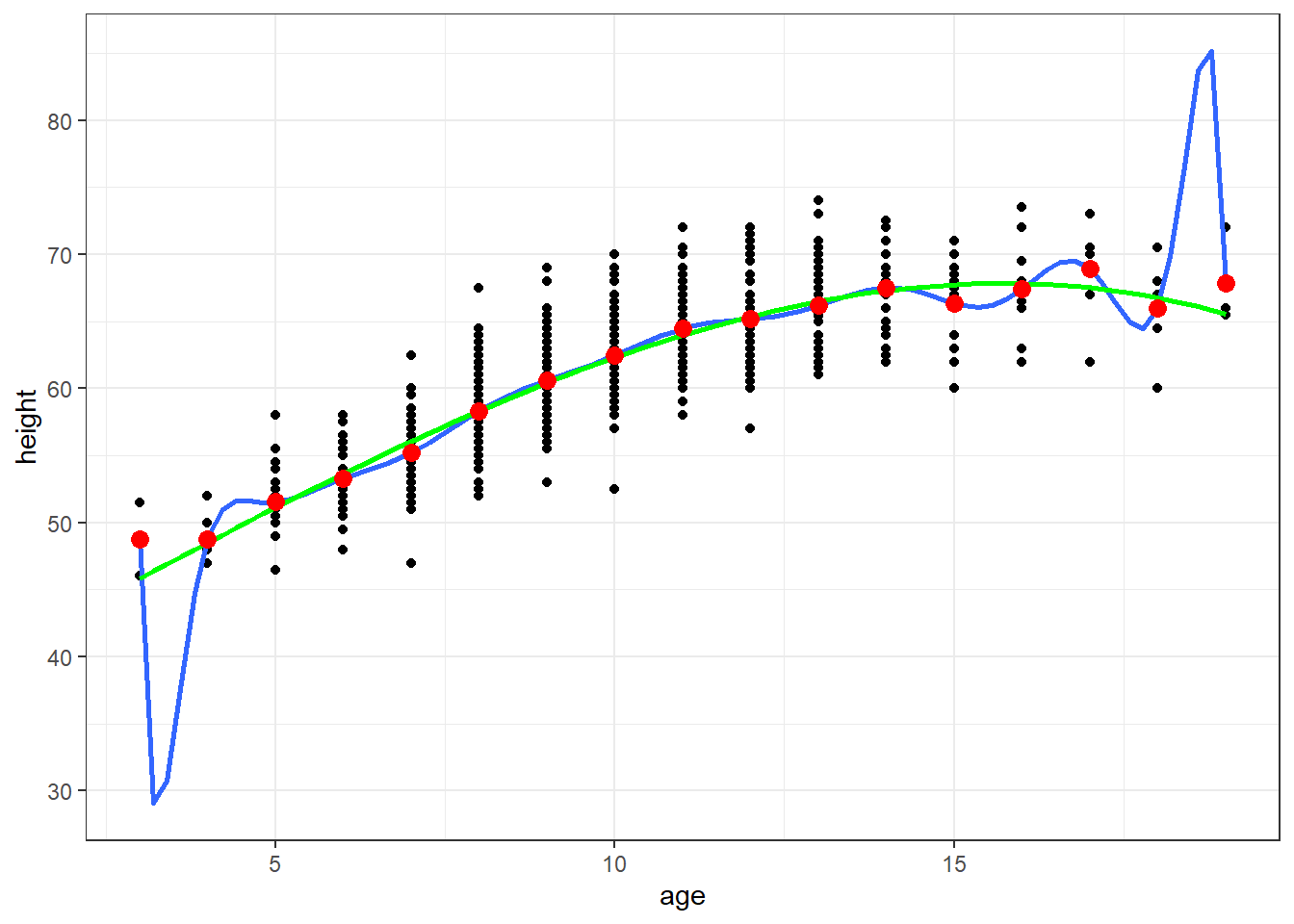

A polynomial of lesser degree could also be considered. I show a model that includes polynomials for age up to degree 3 in the following plot. It is also less stable near the upper and lower bounds of age, but not as obviously so as the 16 degree polynomial.

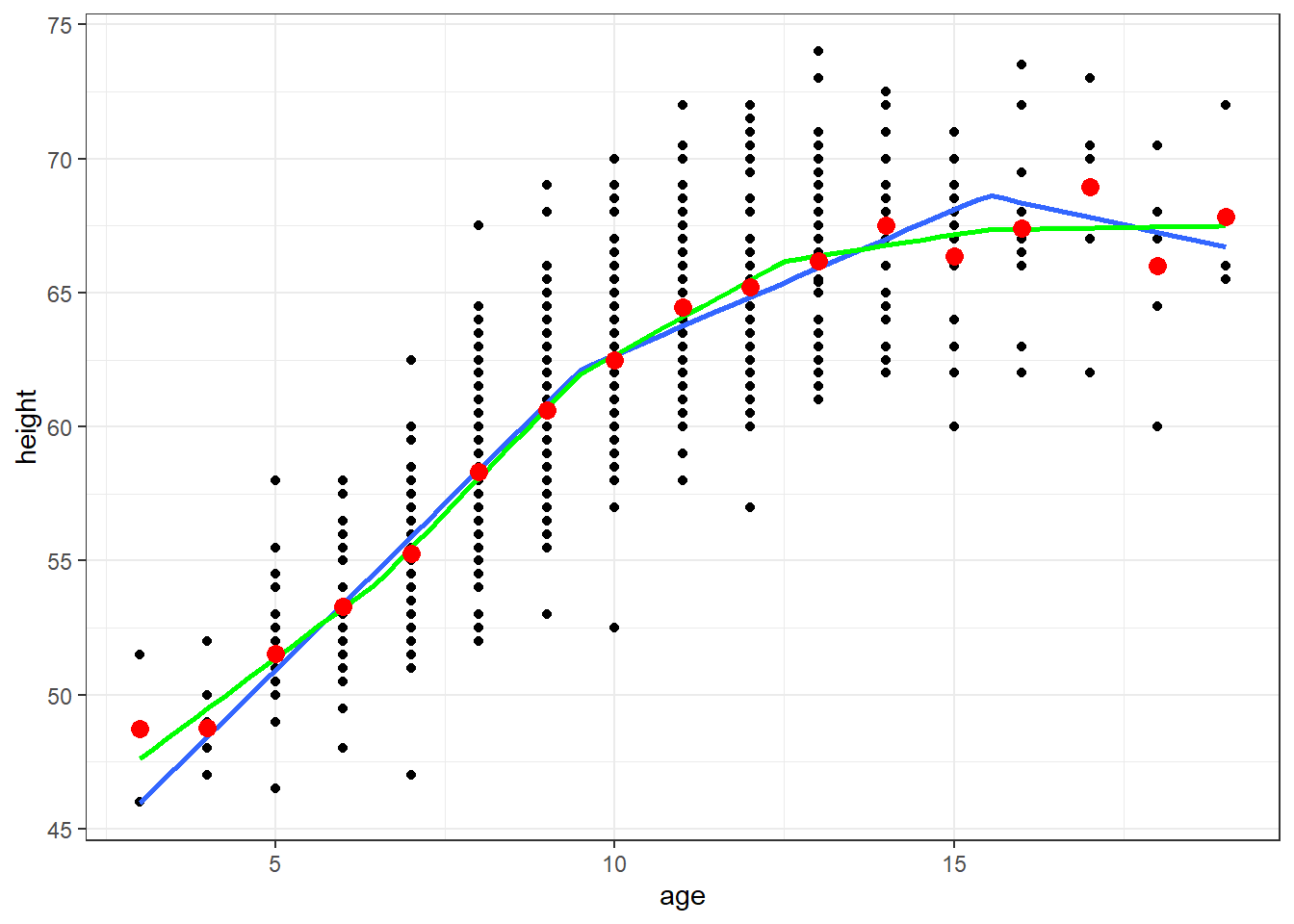

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ poly(x,16), se=FALSE) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ poly(x,3), se=FALSE, col="Green") +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3)

m.poly16 <- lm(height ~ poly(age,16), data=fev)

m.poly3 <- lm(height ~ poly(age,3), data=fev)

newdata$ht.poly16 <- predict(m.poly16, newdata)

newdata$ht.poly3 <- predict(m.poly3, newdata)

newdata[12:17,]| age | ht.dummy | ht.poly16 | ht.poly3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 14 | 67.520 | 67.520 | 67.288 |

| 13 | 15 | 66.368 | 66.368 | 67.745 |

| 14 | 16 | 67.385 | 67.385 | 67.829 |

| 15 | 17 | 68.938 | 68.937 | 67.513 |

| 16 | 18 | 66.000 | 66.000 | 66.768 |

| 17 | 19 | 67.833 | 67.833 | 65.566 |

Piecewise linear curves

Joined at “knots”

Straight lines in between the knots

Convenient parametrizations such that (1) coefficients are slopes of consecutive segments or (2) coefficients are slope changes at consecutive knots

Advantages

Interpretability. Has the interpretation as the slope (or slope change) from the regression model, but within a range of \(X\)

Best to specify know locations in advance for desired scientific interpretation

Nested within a restriced model with a single slope term (hierarchcical structure allow comparisons of complex to simpler models)

Disadvantages

Stata: mkspline newvar0 knot1 newvar1 knot2 newvar2 ... knotp newvarp = oldvar

Would then run regression using newvar0 … newvarp

Assumes straight lines between min and knot1; knot1 and knot2; etc.

In R, we can use the lspline package to make the linear splines

The following results will look at age and height using linear splines with 2 knots and 4 knots

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ lspline(x, knots=c(9.5,15.5)), se=FALSE) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ lspline(x, knots=c(6.5,9.5,12.5,15.5)), se=FALSE, col="Green") +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3)

m.linspline.nonmar <- lm(height ~ lspline(age, knots=c(9.5,15.5)), data=fev)

coeftest(m.linspline.nonmar, varcov=sandwich)| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 38.49107 | 0.813179 | 47.3341 | 0.00000 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))1 | 2.48855 | 0.099940 | 24.9005 | 0.00000 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))2 | 1.08521 | 0.088609 | 12.2472 | 0.00000 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))3 | -0.55308 | 0.371351 | -1.4894 | 0.13687 |

coefci(m.linspline.nonmar, varcov=sandwich)| 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 36.89430 | 40.08785 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))1 | 2.29231 | 2.68480 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))2 | 0.91122 | 1.25921 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))3 | -1.28228 | 0.17611 |

(Intercept) is the expect height when age is 0. Since this is outside the range of our data, it has no scientific interpretation.

The first slope term (‘lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))1’) is the expected change in height comparing two individuals who differ in age by one year when both subjects are 9 years old or less. Comparing two children who are both 3 to 9 years old and differ in age by one year, the older child on average will be 2.49 inches taller than the younger child. We are 95% confident the true difference in height is between 2.29 and 2.68 inches taller.

That is, the model assumes that the change in height comparing 3 to 4, 4 to 5, 5 to 6, 6 to 7, 7 to 8, 8 to 9 is the same (a similar growth rate over these age ranges)

The model borrow strength across the age ranges by assuming the same slope

The model borrows strength across the next age range by assuming the mean height at the knot (9.5 years) is the same at the upper end of first age group and the lower end of the second age group.

The second slope term (‘lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))2’) is the expected change in height comparing two individuals who differ in age by one year when both subjects are between 10 and 15 years old

The third slope term (‘lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))3’) is the expected change in height comparing two individuals who differ in age by one year when both subjects are 16 years old or older

We can test if the age-height slope significantly changes with age category

linearHypothesis(m.linspline.nonmar,

c("lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))1=lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))2",

"lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))1=lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))3"),

vcov=sandwich(m.linspline.nonmar))| Res.Df | Df | F | Pr(>F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 652 | |||

| 650 | 2 | 85.721 | 0 |

We reject the null hypothesis (\(P<0.001\)) and conclude the linear spline model is a better fit than the restricted model, \(E[Height | Age = a] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 * a\)

The following is the basis matrix for the linear spline (non-marginal) for ages 3 to 19. It is relatively easy to calculate this matrix

cbind(3:19, lspline(3:19, knots = c(9.5, 15.5)))| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 9 | 9.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 10 | 9.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| 11 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| 12 | 9.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 |

| 13 | 9.5 | 3.5 | 0.0 |

| 14 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 0.0 |

| 15 | 9.5 | 5.5 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 0.5 |

| 17 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 1.5 |

| 18 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 2.5 |

| 19 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 3.5 |

m.linspline.mar <- lm(height ~ lspline(age, knots=c(9.5,15.5), marginal=TRUE), data=fev)

coeftest(m.linspline.mar, varcov=sandwich)| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 38.4911 | 0.81318 | 47.3341 | 0.00000000 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)1 | 2.4886 | 0.09994 | 24.9005 | 0.00000000 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)2 | -1.4033 | 0.16335 | -8.5911 | 0.00000000 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)3 | -1.6383 | 0.42028 | -3.8981 | 0.00010701 |

coefci(m.linspline.mar, varcov=sandwich)| 2.5 % | 97.5 % | |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 36.8943 | 40.08785 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)1 | 2.2923 | 2.68480 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)2 | -1.7241 | -1.08259 |

| lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)3 | -2.4636 | -0.81303 |

(Intercept) is the expect height when age is 0. Since this is outside the range of our data, it has no scientific interpretation.

The first slope term (‘lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))1’) is the expected change in height comparing two individuals who differ in age by one year when both subjects are 9 years old or less.

The second slope term (‘lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))2’) is the change in the age-height slope for 10 to 15 year olds versus 3 to 9 year olds. This output is useful for estimating and testing the slope changes over age.

The third slope term (‘lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5))3’) is the change in the age-height slope for 16 to 19 year olds versus 3 to 9 year olds. This output is useful for estimating and testing the slope changes over age.

Using this model, we can test if the age-height slope significantly changes with age category

linearHypothesis(m.linspline.mar,

c("lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)2",

"lspline(age, knots = c(9.5, 15.5), marginal = TRUE)3"),

vcov=sandwich(m.linspline.mar))| Res.Df | Df | F | Pr(>F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 652 | |||

| 650 | 2 | 85.721 | 0 |

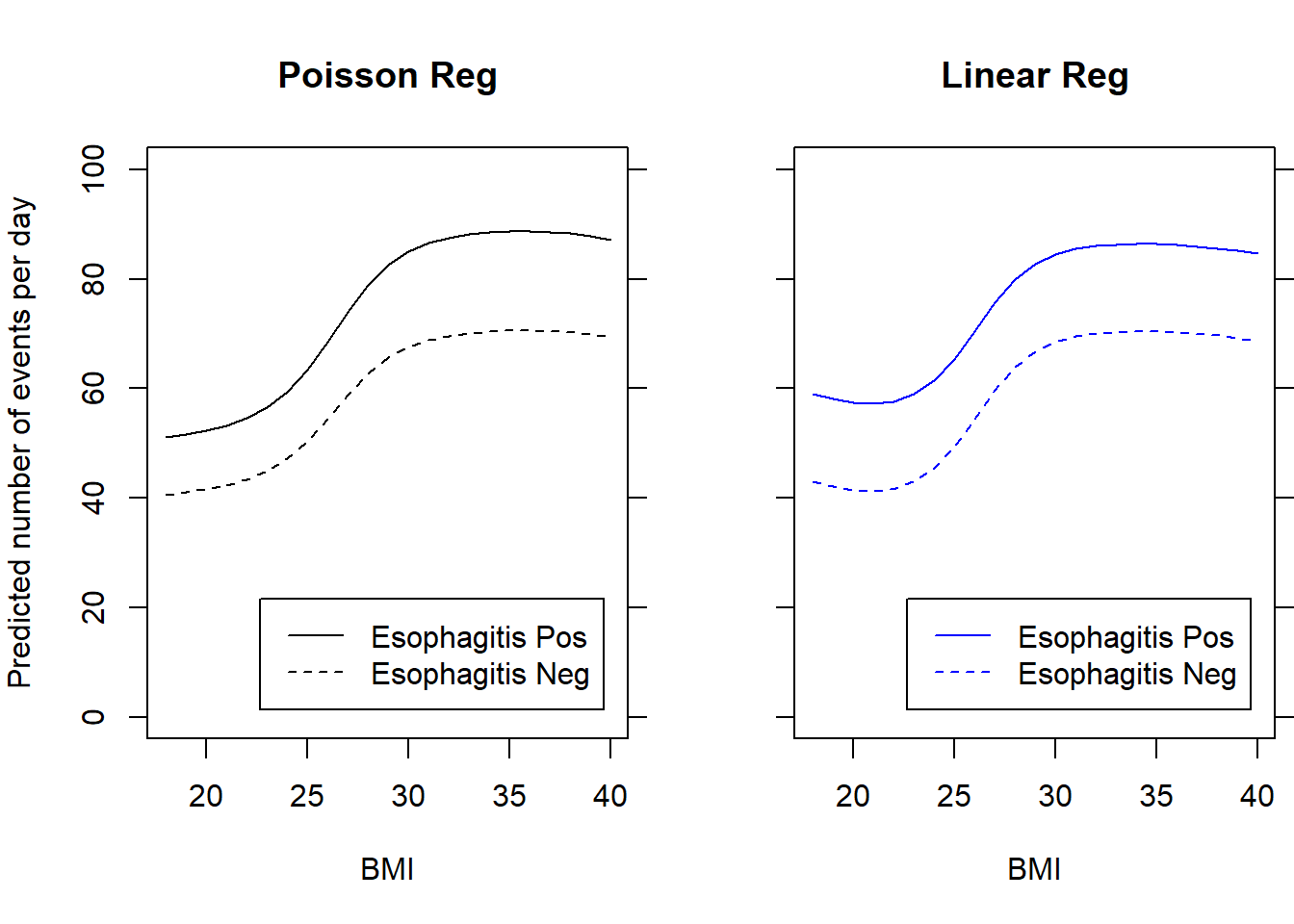

Polynomial splines introduces squared or cubic terms to increase the smoothness of the estimate. In particular, compare to linear splines, they are no abrupt changes in the slope at each knot point.

There are various types of polynomial splines, each with different formulas applied to generate the basis matrix for the regression model

We can choose to modify several parameters, depending on the function

Number of knots

Where to place the knots (or use defaults based on quantiles and number of knots)

Degree of the polynomial. In practice, rarely is a degree over 3 considered

Increasing the number of knots and the degree of the polynomial will increase the flexibility of the model

Several different comparisons are shown in the following plots

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ poly(x, 3), se=FALSE, aes(color="Blue")) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ bs(x,3), se=FALSE, aes(col="Green")) +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="Red", size=3) +

scale_colour_manual(name="Model", values=c("Blue", "Green"), labels=c("poly(x,3)","bs(x,3)")) + theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.2))

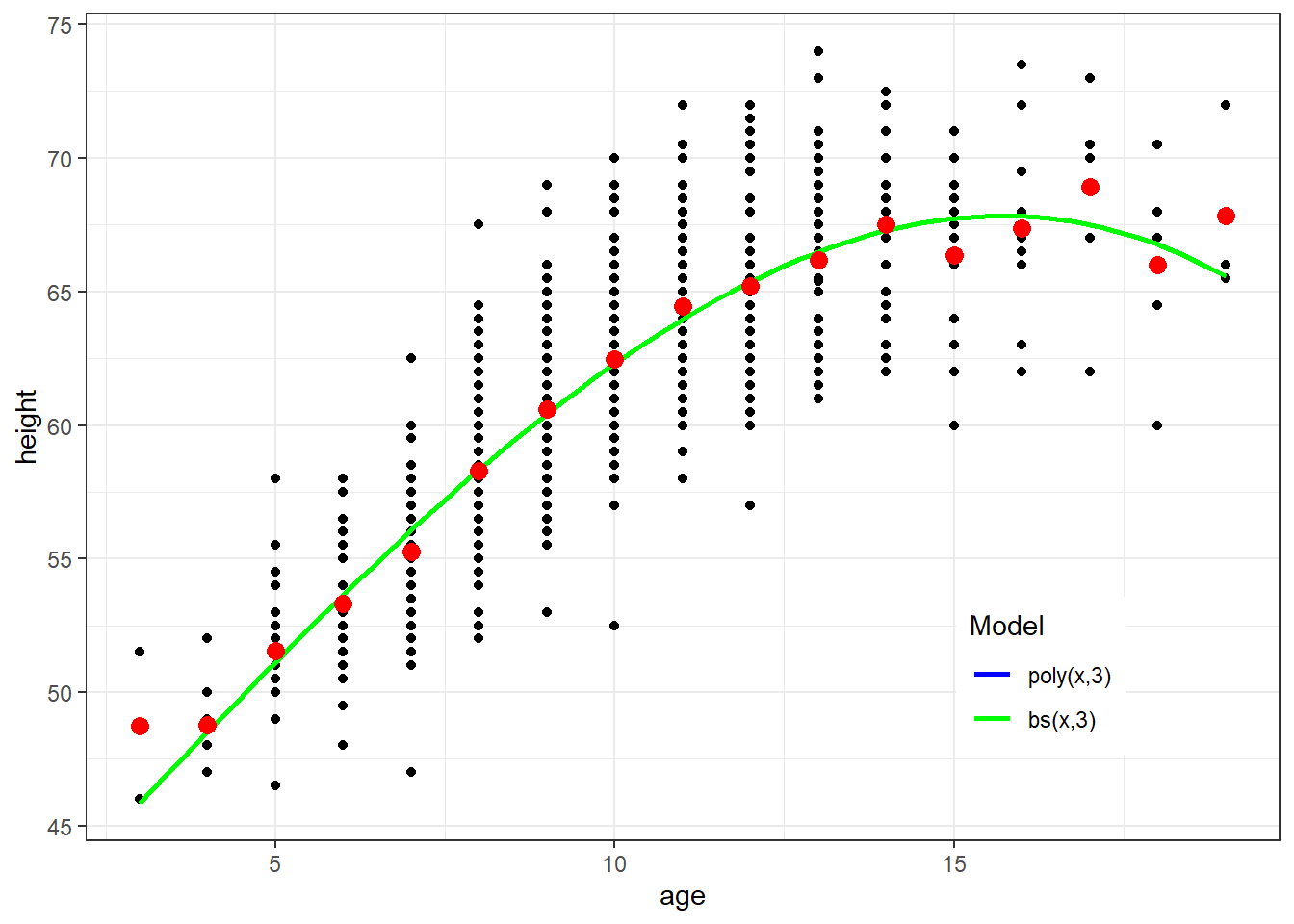

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ lspline(x,knots=c(9.5, 15.5)), se=FALSE, aes(color="Blue")) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ bs(x,knots=c(9.5, 15.5), degree=3), se=FALSE, aes(color="Green")) +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3) +

scale_colour_manual(name="Model", values=c("Blue", "Green"), labels=c("lspline(x,knots=c(9.5, 15.5))","bs(x,knots=c(9.5, 15.5)")) + theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.2))

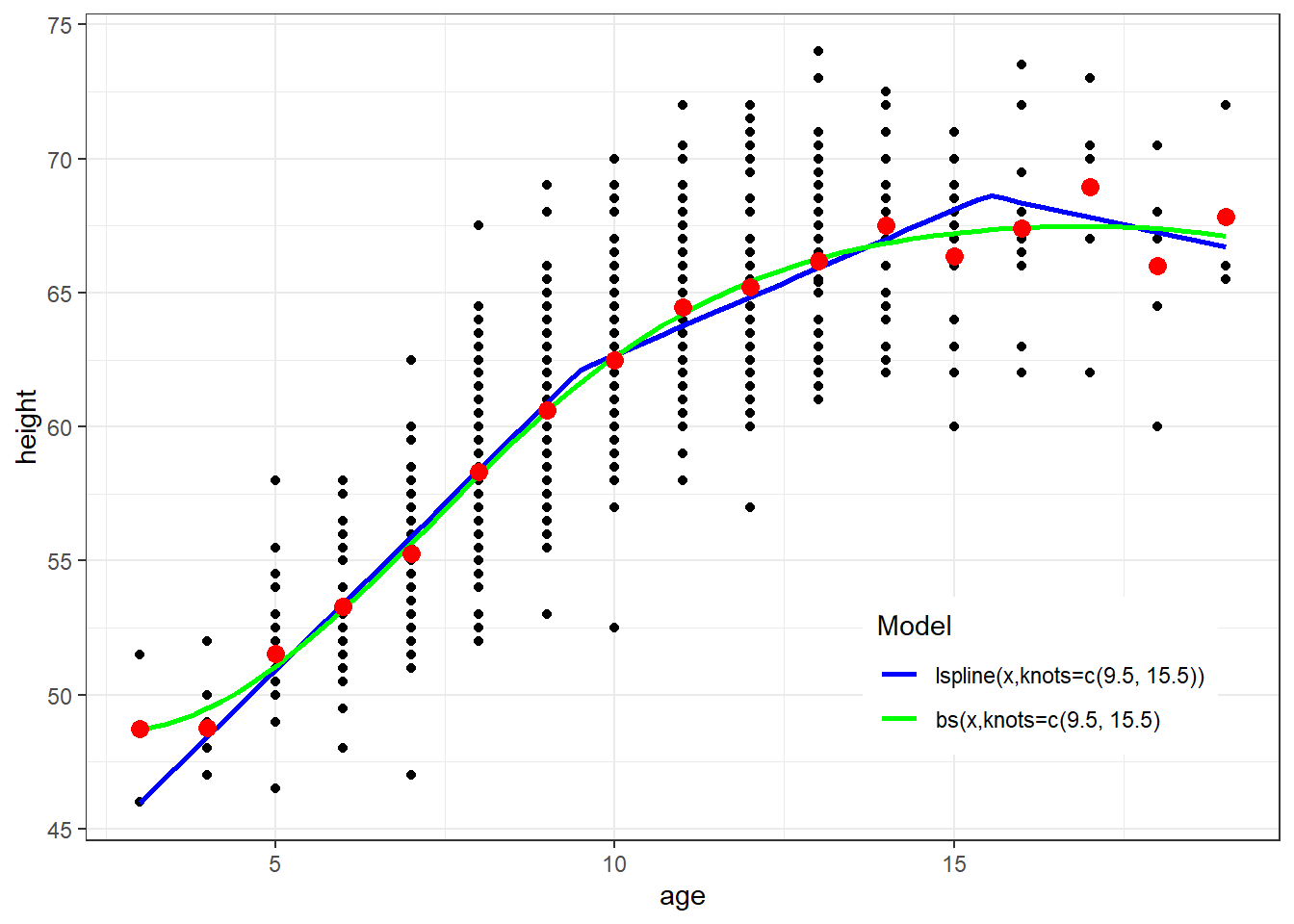

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ ns(x, df=3), se=FALSE, aes(color="Blue")) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ bs(x,3, knots=c(9.5, 15.5)), se=FALSE, aes(color="Green")) +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3)+

scale_colour_manual(name="Model", values=c("Blue", "Green"), labels=c("ns(x, df=3)","bs(x,3, knots=c(9.5, 15.5)")) + theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.2))

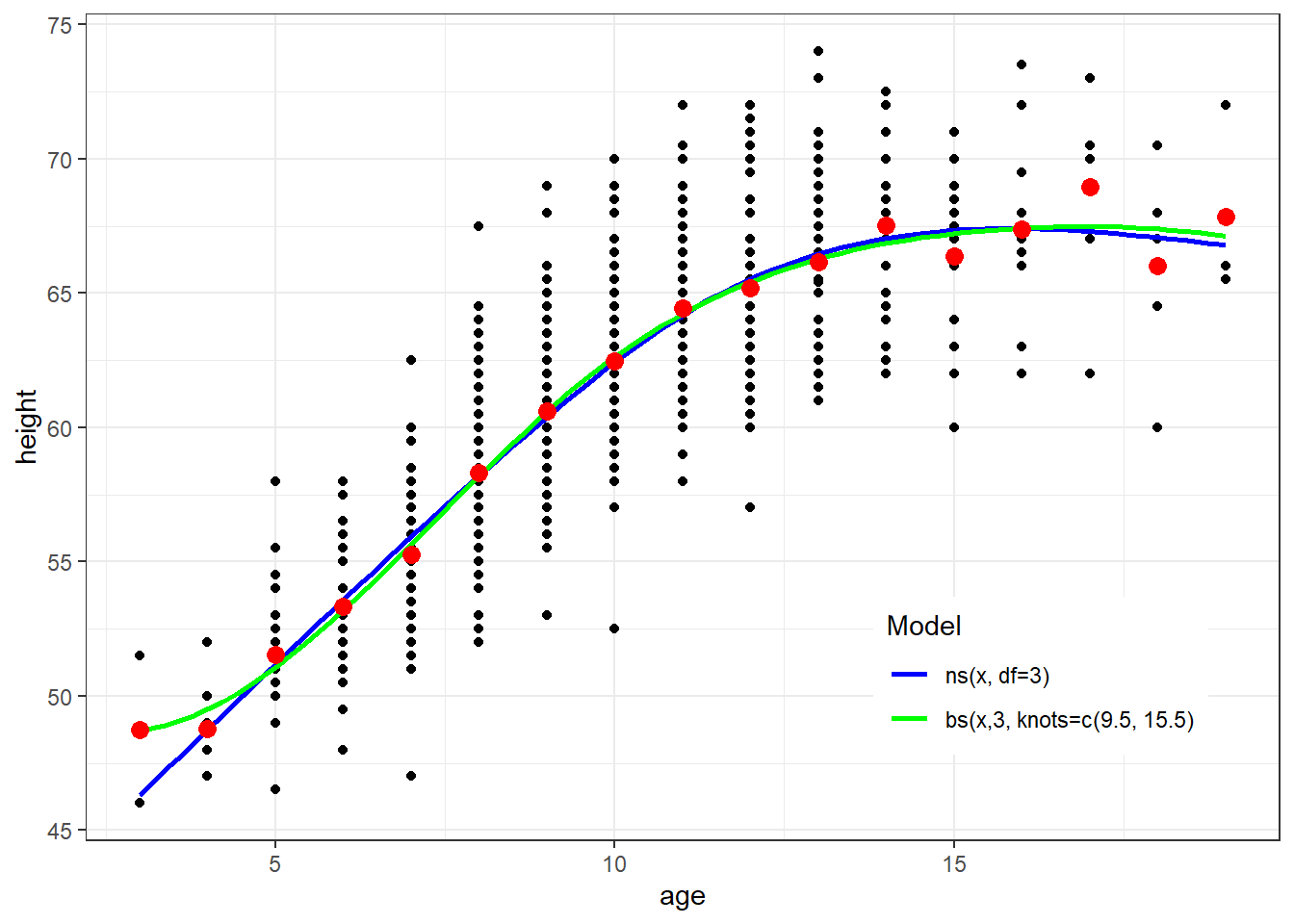

Natural splines and restricted cubic spline are both cubic splines with restrictions of linearity beyond the boundary knot locations

They have different inputs which can result in different model fits

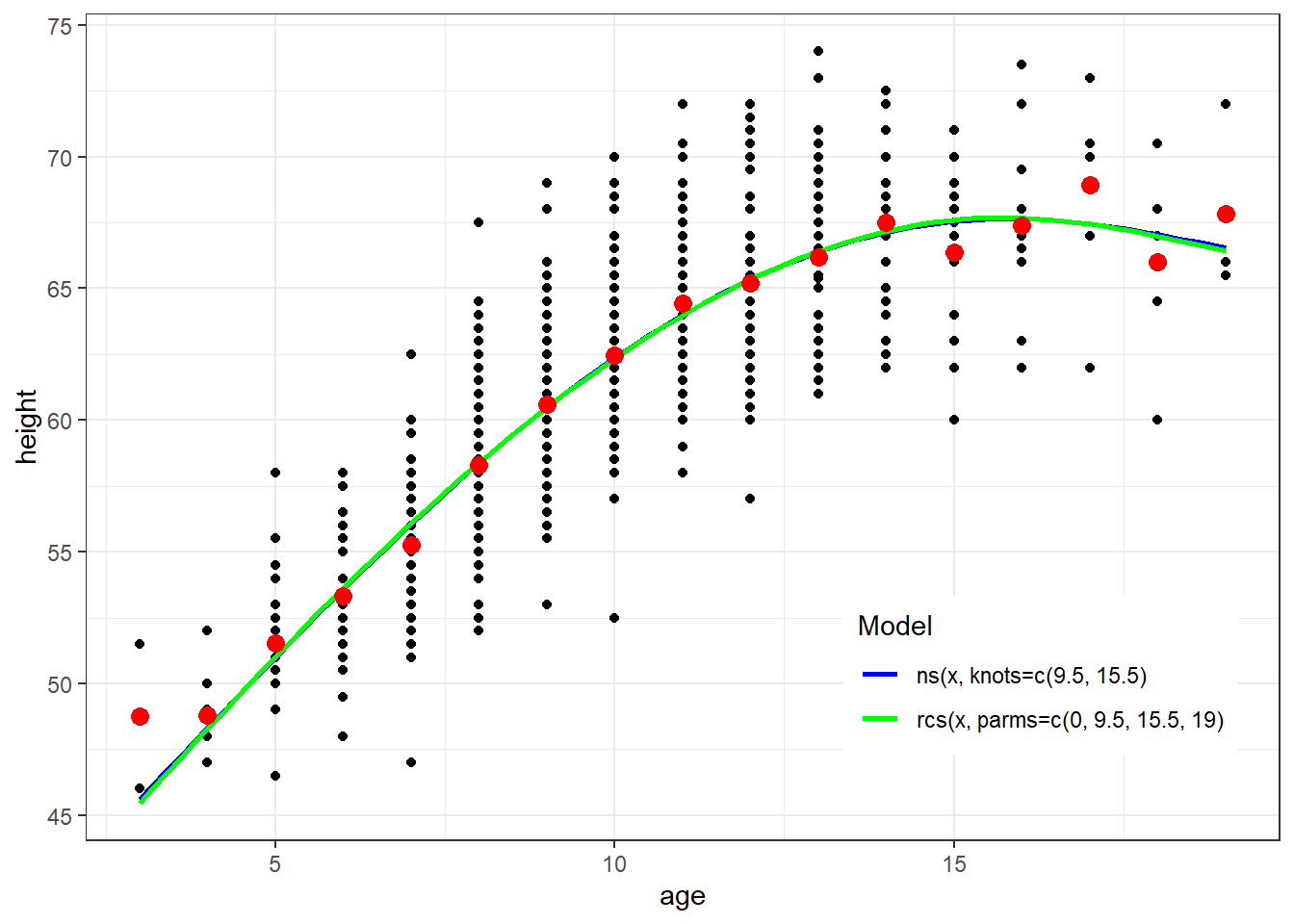

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ ns(x, knots=c(9.5, 15.5)), se=FALSE, aes(color="Blue")) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ rcs(x, parms=c(0, 9.5, 15.5, 19)), se=FALSE, aes(color="Green")) +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3) +

scale_colour_manual(name="Model", values=c("Blue", "Green"), labels=c("ns(x, knots=c(9.5, 15.5)","rcs(x, parms=c(0, 9.5, 15.5, 19)")) + theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.2))

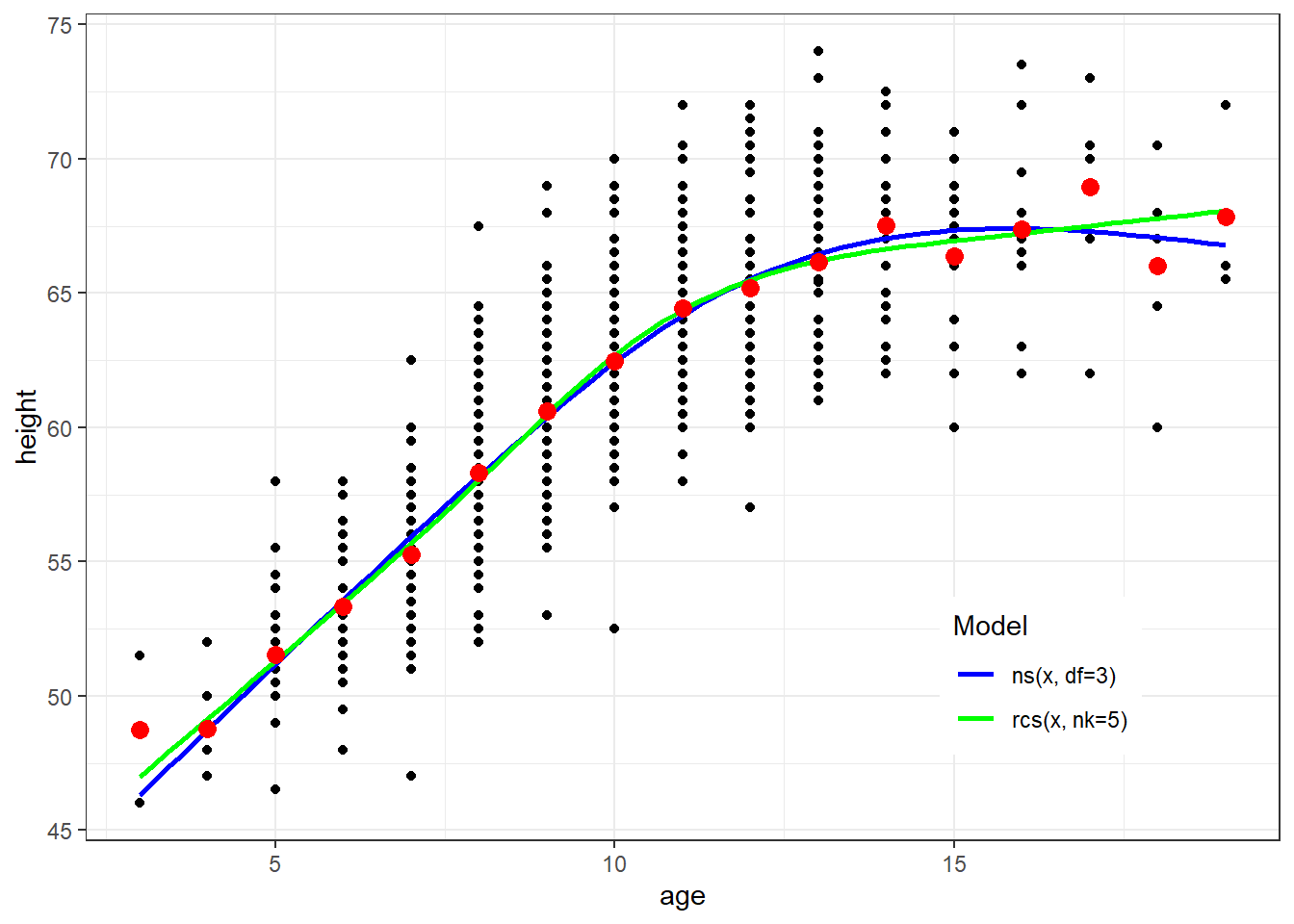

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ ns(x, df=3), se=FALSE, aes(color="Blue")) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ rcs(x, nk=5), se=FALSE, aes(color="Green")) +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3) +

scale_colour_manual(name="Model", values=c("Blue", "Green"), labels=c("ns(x, df=3)","rcs(x, nk=5)")) + theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.2))

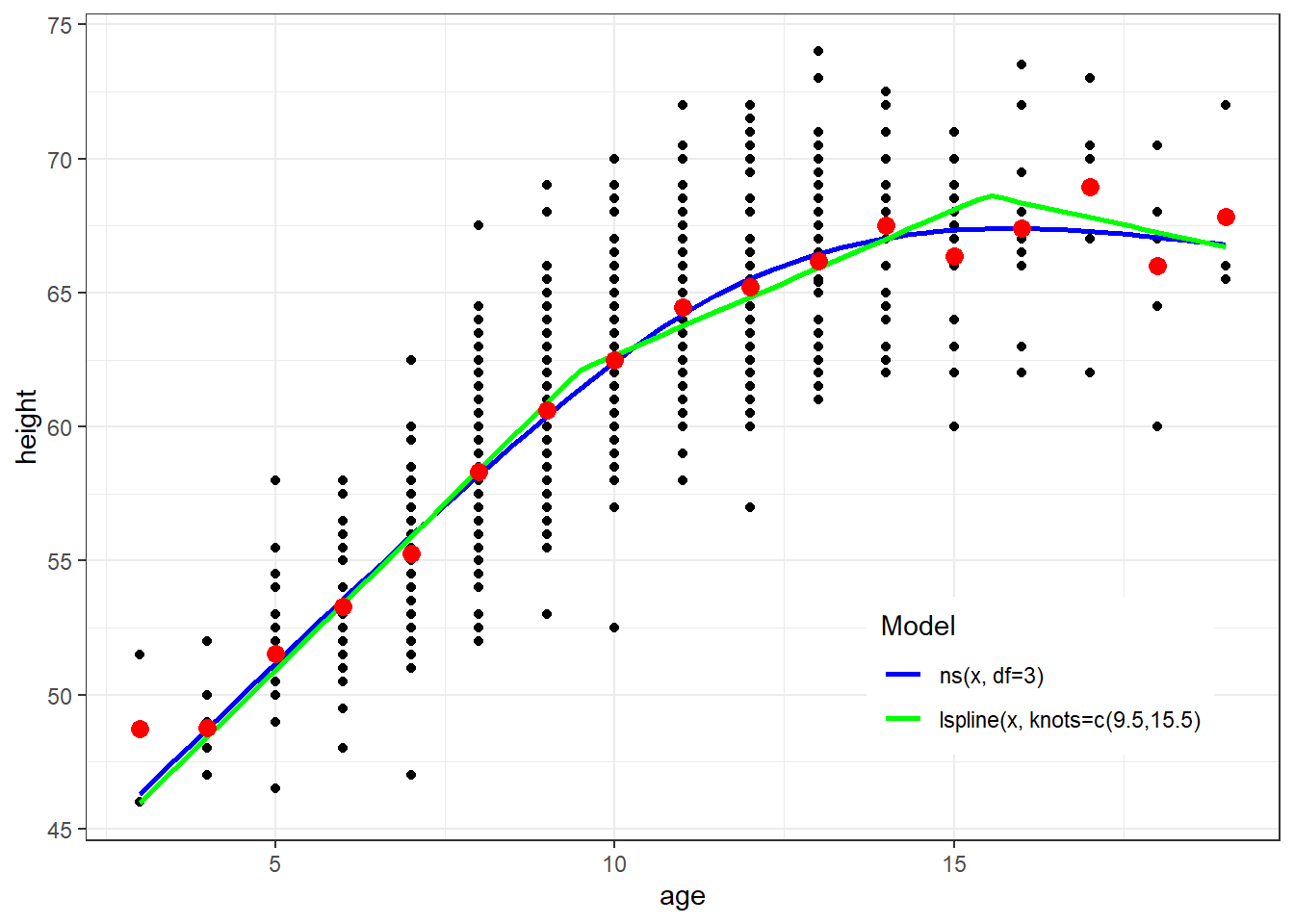

ggplot(fev, aes(x=age, y=height)) + geom_point() + theme_bw() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ ns(x, df=3), se=FALSE, aes(color="Blue")) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ lspline(x, knots=c(9.5,15.5)), se=FALSE, aes(color="Green")) +

geom_point(data=newdata, aes(x=age, y=ht.dummy), col="red", size=3) +

scale_colour_manual(name="Model", values=c("Blue", "Green"), labels=c("ns(x, df=3)","lspline(x, knots=c(9.5,15.5)")) + theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.2))

There are a variety of methods for flexibly modeling continuous covariates

Approach you use should be pre-specified and based on scientific considerations

Splines for predictor of interest in an association study

If you want to be able to write numerical summaries of your results, consider piecewise linear splines

May provide an adequate summary of your results, particularly for comparison between two knots

Comparison between subgroups separated by a knot location more challenging as you have a change in slope

Formal test can be conducted to determine if the slope is significantly different on ranges of \(X\) (hierarchical models)

Best to pre-specify your knot locations based on relevant scientific meaning

Lacking scientific reasons, it is OK to use quantiles as the quantiles are not related to the outcome (unsupervised learning)

Should not pick knot locations after looking at the outcome unless you have a plan for how to adjust your analysis for making data-driven decision (this type of adjustment is hard to do, so I recommend avoiding it)

Spline for estimating means or prediction of new observations

Flexible methods most appropriate in this approach

Be careful of behavior of your splines at the extremes of your continuous covariates

Degrees of freedom, or allowed model complexity needs to be considered in terms of the effective sample size for the type of outcome you are studying

Effective sample sizes

Allowed model complexity is, roughly, gain one available degree of freedom per every 10-15 of effective sample size

Degrees of freedom can be spent on dummy variable, knot locations, and degree of polynomial

Degrees of freedom can be saved by constraints, such as the linearity constraint at the tails for natural splines and restricted cubic spline. These are popular splines because the constraint often saves degrees of freedom while improving the generalizability of the fit at the tails of the continuous distribution

These are approximatione, and the allowed model complexity can depend on other characteristics of the data too

Splines for effect modification (continuous effect modifier and/or continuous predictor of interest)

Choice of model should be dictated by scientific considerations first

Statistically, we have limited power to detect effect modification

Linear terms for modeling effect modification may suffice

Flexible models for a precision variable

Often most of the association of the precision variable with the outcome can be capture in a linear term

However, if justified, can consider a flexible model too

Goal of a precision variable is to explain residual variability in the outcome after accounting for the predictor of interest (and, possibly, confounders that are included in the model)

Flexible models for confounders

Often it is important to adjust for confounders adequately, so a spline or other flexible function can help

If we are not interested in interpreting the effect of the confounder, then we are free to model it a variety of different ways

Argues for flexibly modeling continuous confounder (limited by the effective sample size)

Note that if the confounder effect really is a straight line, then a cubic spline with linearity constraints on the tails should also fit adequately

There is not much to be lost and potentially much to be gained by pre-specifying a flexible model for a continuous confounder

If it is a straight line, a flexibly spline or a linear tearm can capture the association (either would adjust for confounding)

If it is not a straight line, a flexible spline can capture the assocation while a linear term cannot (spline would more completly adjust for confouding)

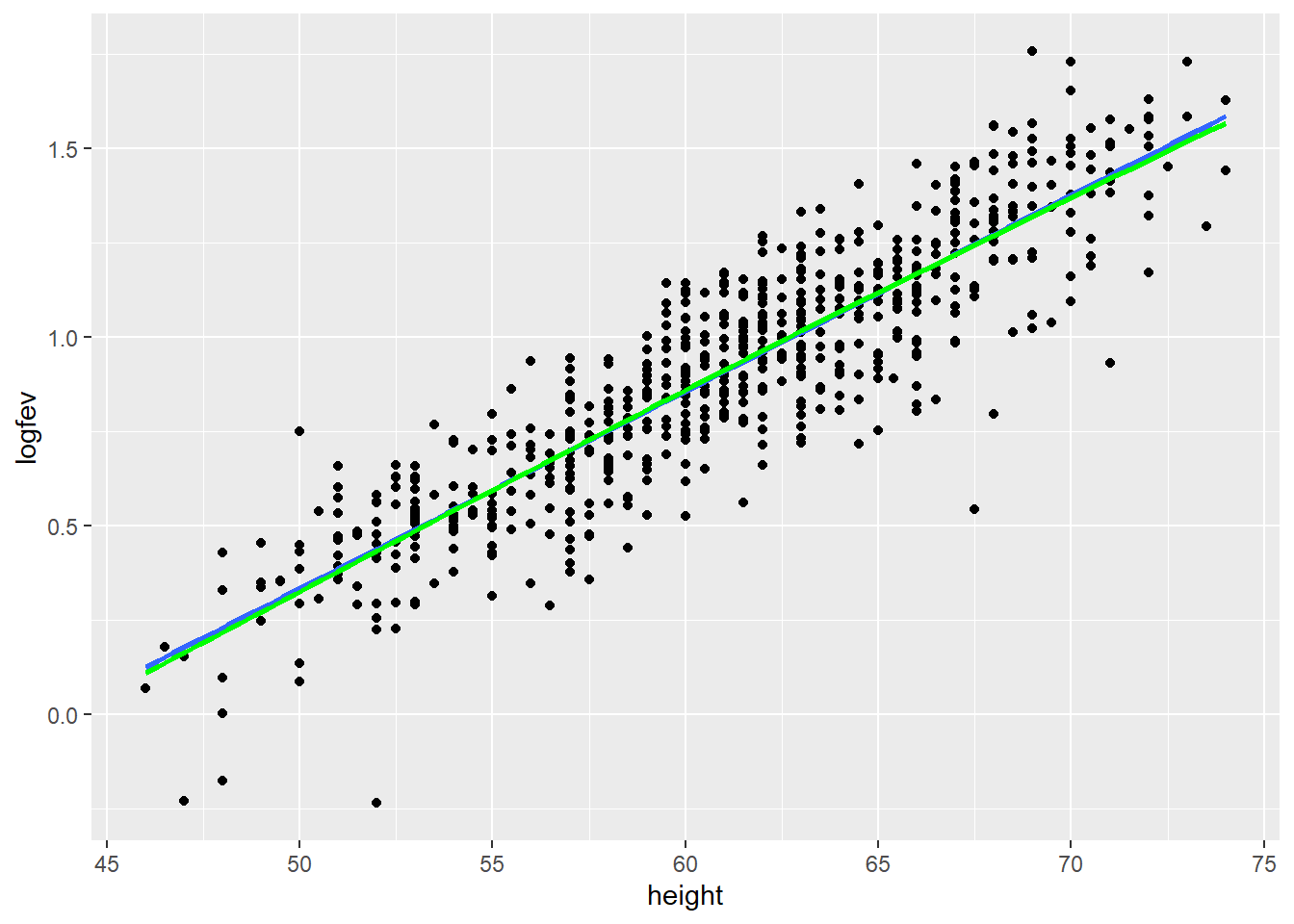

ggplot(fev, aes(x=height, y=logfev)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(method=lm, se=FALSE) +

geom_smooth(method=lm, formula=y ~ ns(x, df=3), se=FALSE, color="Green")

nrow(fev) / 15[1] 43.6fev$smoker <- (fev$smoke=="current smoker")+0

fev$male <- (fev$sex=="male")+0

m1 <- lm(fev ~ smoker + ns(age,3) + ns(height,3) + male, data= fev)

coeftest(m1, vcov=sandwich(m1))| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.090121 | 0.071522 | 15.2418 | 0.0000e+00 |

| smoker | -0.147092 | 0.076797 | -1.9153 | 5.5892e-02 |

| ns(age, 3)1 | 0.494765 | 0.102371 | 4.8330 | 1.6823e-06 |

| ns(age, 3)2 | 0.506067 | 0.205409 | 2.4637 | 1.4011e-02 |

| ns(age, 3)3 | 0.807844 | 0.147608 | 5.4729 | 6.3400e-08 |

| ns(height, 3)1 | 1.430324 | 0.088439 | 16.1731 | 0.0000e+00 |

| ns(height, 3)2 | 3.262242 | 0.215641 | 15.1281 | 0.0000e+00 |

| ns(height, 3)3 | 2.709726 | 0.158847 | 17.0588 | 0.0000e+00 |

| male | 0.096504 | 0.033492 | 2.8814 | 4.0906e-03 |

The betas for the naturally-splined terms (age, height) are difficult to interpret directly. We could test for age and or height effect if that was of scientific interest using the Wald approach.

For the predictor of interest, smoker, we have the usual interpretation in terms of holding other covariates constant. “Among subjects of the same age, height, and sex but differing in smoking status…” However, we may be controlling for the confounding effects of age and height effects more completely by using flexible spline functions.