Code

library(rstanarm)

library(bayesplot)

library(finalfit)

library(dplyr)

library(rms)

library(ggplot2)

library(gglm)

tryCatch(source('pander_registry.R'), error = function(e) invisible(e))Lecture 03

December 8, 2025

library(rstanarm)

library(bayesplot)

library(finalfit)

library(dplyr)

library(rms)

library(ggplot2)

library(gglm)

tryCatch(source('pander_registry.R'), error = function(e) invisible(e))Many statistical problems examine the association between two variables

Outcome variable (response variable, dependent variable)

Grouping variable (covariate, predictor variable, independent variable)

(While “dependent variable” and “independent variable” are commonly used, these imply that a modifiable independent variable is causing a dependent variable to change. We are fitting models focused on association, not causation.)

General goal is to compare distribution of the outcome variable across levels of the grouping variable

Groups are defined by the grouping variable

In intro course, statistical analysis is characterized by two factors

Number of groups (samples)

If subjects in groups are independent

In the two variable setting, statistical analysis is more generally characterized by the grouping variable. If the grouping variable is

Constant: One sample problem

Binary: Two sample problem

Categorical: \(k\) sample problem (e.g. ANOVA)

Continuous: Infinite sample problem (analyzed with regression)

Regression thus extends the one- and two-sample problems up to infinite sample problems

Of course, in reality we never have infinite samples, but models that can handle this case are the ultimate generalization

Continuous predictors of interest

Continuous adjustment variables

### Make a cholesterol and age dataframe. Set the random number seed so everything is reproducible

set.seed(19)

plotdata <- data.frame(age=c(63, 63, rep(65:80,15), rep(81:85,10), 86,86,86, 87,89, 90, 93, 95, 100),

chol=NA)

plotdata$chol <- 190 + .5*plotdata$age + rnorm(length(plotdata$age), 0, 15)

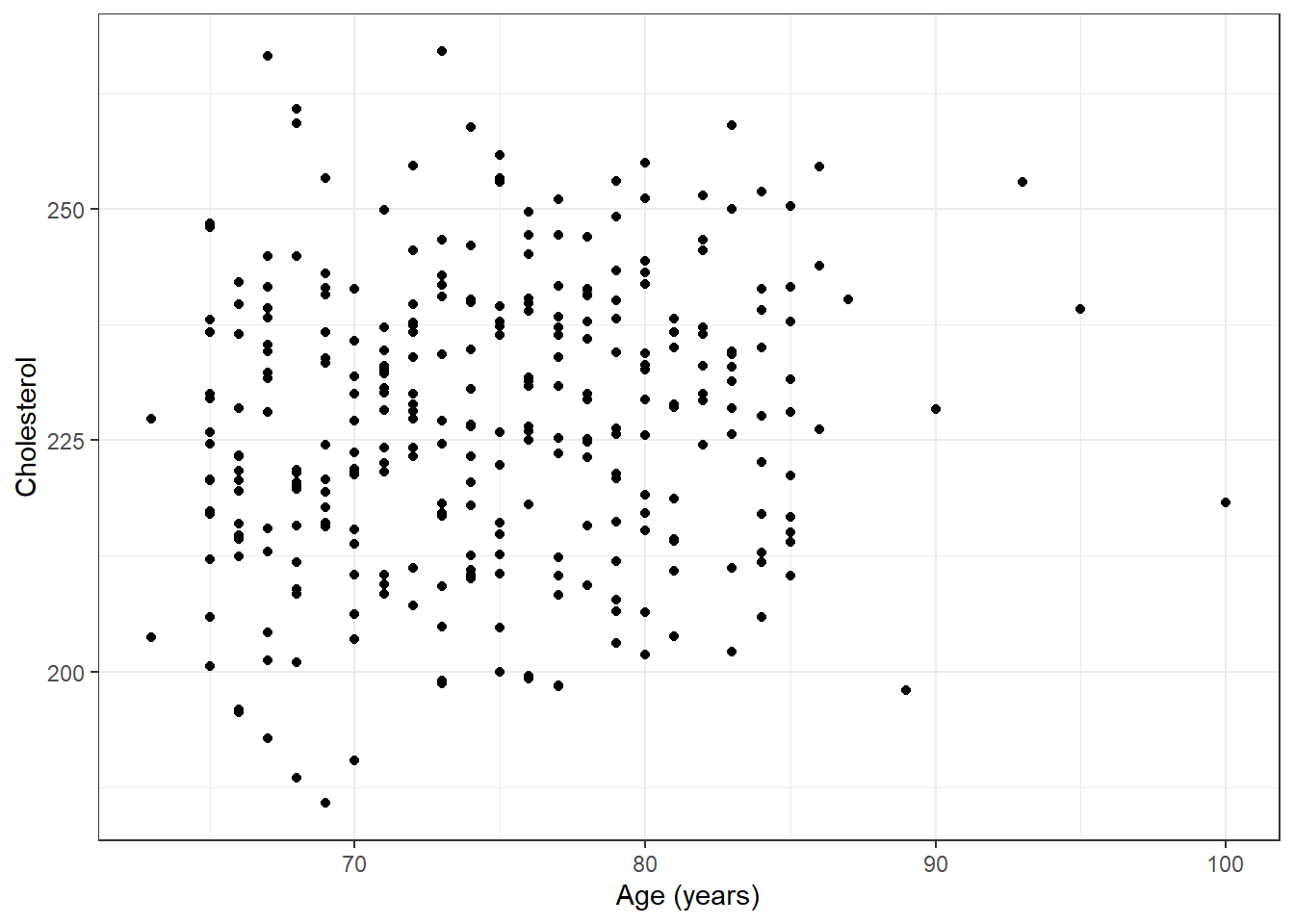

ggplot(plotdata, aes(x=age, y=chol)) + geom_point() + ylab("Cholesterol") + xlab("Age (years)") + theme_bw()

With a binary grouping variable, regression models reduce to the corresponding two variable methods

Linear regression with a binary predictor

Logistic regression with a binary predictor

Proportional odds regression with a binary predictor

Cox (proportional hazards) regression with a binary predictor

Is there an association between cholesterol and age?

Scientific question: Does aging effect cholesterol?

Statistical question: Does the distribution of cholesterol differ across age groups?

Acknowledges variability in the response (cholesterol)

Acknowledges cause-effect relationship is uncertain

Association does not imply causation

Continuous response variable: Cholesterol

Continuous grouping variable (predictor of interest): Age

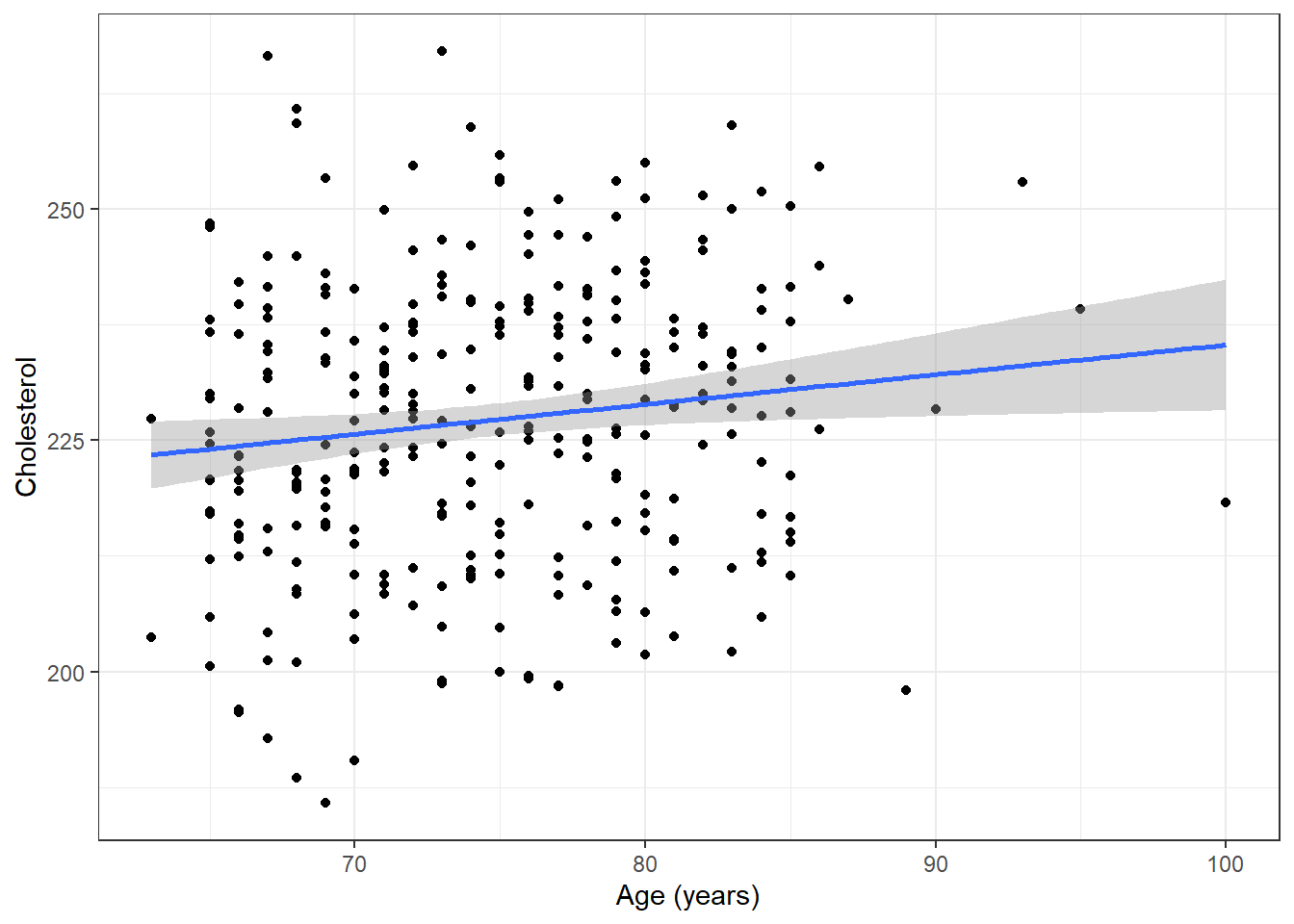

Attempt to answer scientific question by assessing linear trends in average cholesterol

Estimate the best fitting line to average cholesterol within age groups

\[ E[\textrm{Chol} | \textrm{Age}] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times \textrm{Age} \]

The expected value of cholesterol given age is modeled using an intercept (\(\beta_0\)) and slope (\(\beta_1\))

An association exists if the slope is nonzero

A non-zero slope indicates that the average cholesterol will be different across different age groups

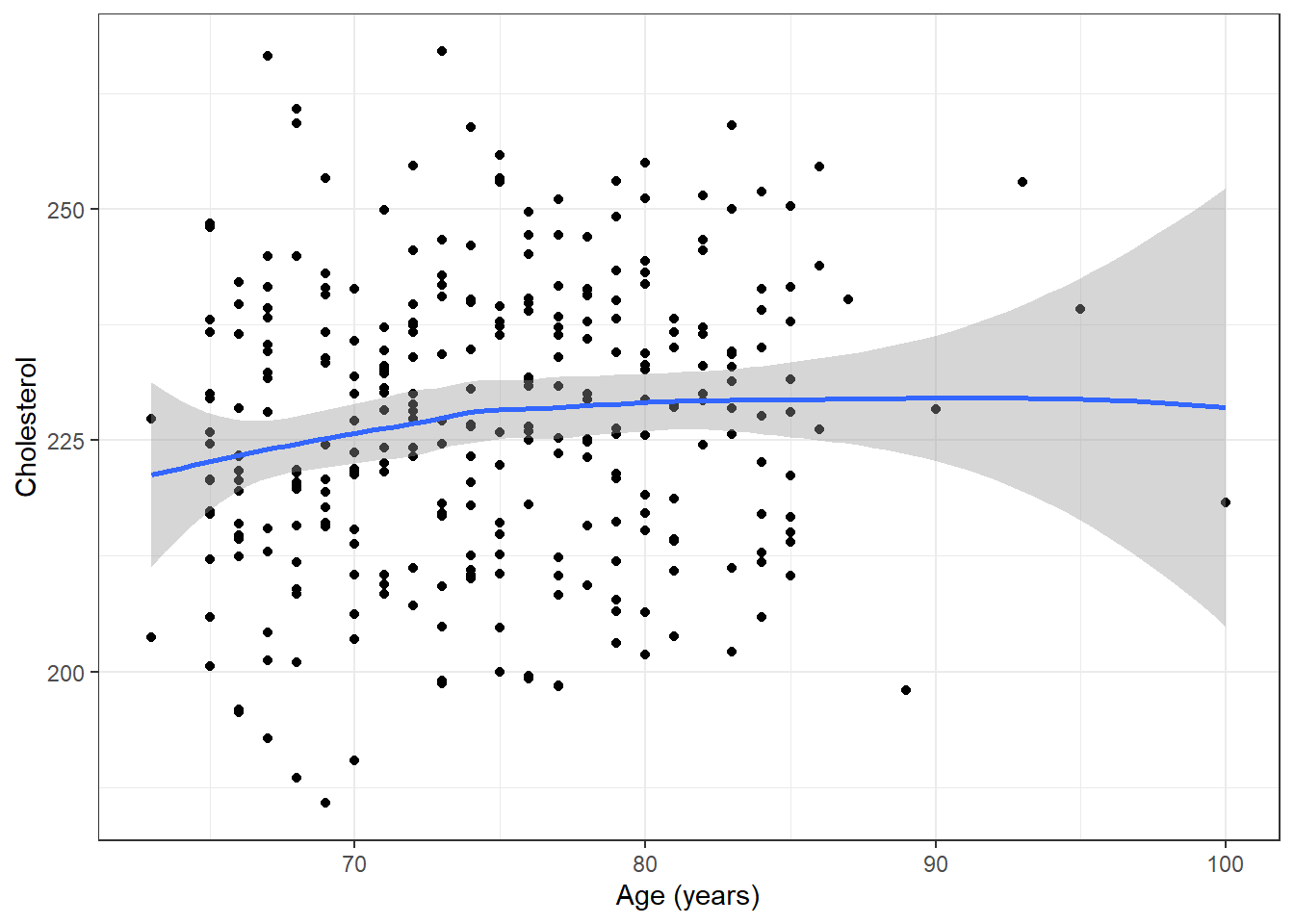

ggplot(plotdata, aes(x=age, y=chol)) + geom_point() + ylab("Cholesterol") + xlab("Age (years)") + theme_bw() + geom_smooth()

ggplot(plotdata, aes(x=age, y=chol)) + geom_point() + ylab("Cholesterol") + xlab("Age (years)") + theme_bw() + geom_smooth(method="lm")

The simple regression model produces an easy to remember (but approximate) rule of thumb.

“Normal cholesterol is 190 plus half your age”

\(E[\textrm{Chol} | \textrm{Age}] = 190 + 0.50 \times \textrm{Age}\)

Note that data were generated using this model. Estimates, below, will be different.

m.chol <- lm(chol ~ age, data=plotdata)

summary(m.chol)

Call:

lm(formula = chol ~ age, data = plotdata)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-39.591 -10.524 -0.234 11.154 41.819

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 203.2259 10.3138 19.704 <2e-16 ***

age 0.3209 0.1375 2.333 0.0203 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 15.34 on 299 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.01788, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0146

F-statistic: 5.444 on 1 and 299 DF, p-value: 0.0203confint.default(m.chol, "age") # Based on asymptotic Normality 2.5 % 97.5 %

age 0.051334 0.5904842\(E[\textrm{Chol} | \textrm{Age}] = 203.2 + 0.32 \times \textrm{Age}\)

explanatory = c("age")

dependent = 'chol'

label(plotdata$chol) <- "Cholesterol"

label(plotdata$age) <- "Age (years)"

finalfit(plotdata, dependent, explanatory) Dependent: Cholesterol unit value

Age (years) [63.0,100.0] Mean (sd) 227.2 (15.5)

Coefficient (univariable) Coefficient (multivariable)

0.32 (0.05 to 0.59, p=0.020) 0.32 (0.05 to 0.59, p=0.020)Bayesian approach to the linear model requires specifying

The model, e.g. a linear model with intercept and slope for age, Normally distributed errors and constant variance

Prior distributions on parameters

For the simple linear regression model, we have parameters \(\beta_0\), \(\beta_1\), and \(\sigma\).

For now, we will use default prior distributions that are are intended to be weakly informative in that they provide moderate regularization and help stabilize computation. See the STAN documentation for more details

Appropriate priors can be based on scientific considerations

Sensitivity analyses can evaluate the the robustness of finding to different prior assumptions

Output from Bayesian linear regression

fit1 <- stan_glm(chol ~ age,

data=plotdata, family=gaussian(),

seed=1234,

refresh=0)

summary(fit1, digits=2, prob=c(.025, .5, .975))

Model Info:

function: stan_glm

family: gaussian [identity]

formula: chol ~ age

algorithm: sampling

sample: 4000 (posterior sample size)

priors: see help('prior_summary')

observations: 301

predictors: 2

Estimates:

mean sd 2.5% 50% 97.5%

(Intercept) 203.28 10.69 182.56 203.18 224.80

age 0.32 0.14 0.04 0.32 0.60

sigma 15.39 0.63 14.25 15.37 16.74

Fit Diagnostics:

mean sd 2.5% 50% 97.5%

mean_PPD 227.19 1.24 224.79 227.19 229.63

The mean_ppd is the sample average posterior predictive distribution of the outcome variable (for details see help('summary.stanreg')).

MCMC diagnostics

mcse Rhat n_eff

(Intercept) 0.18 1.00 3721

age 0.00 1.00 3735

sigma 0.01 1.00 3469

mean_PPD 0.02 1.00 3911

log-posterior 0.03 1.00 1638

For each parameter, mcse is Monte Carlo standard error, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size, and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence Rhat=1).prior_summary(fit1, digits = 2)Priors for model 'fit1'

------

Intercept (after predictors centered)

Specified prior:

~ normal(location = 227, scale = 2.5)

Adjusted prior:

~ normal(location = 227, scale = 39)

Coefficients

Specified prior:

~ normal(location = 0, scale = 2.5)

Adjusted prior:

~ normal(location = 0, scale = 6)

Auxiliary (sigma)

Specified prior:

~ exponential(rate = 1)

Adjusted prior:

~ exponential(rate = 0.065)

------

See help('prior_summary.stanreg') for more detailsInterpretation

Slope for age is of primary scientific importance

A priori we assume that no association between age and cholesterol. Specifically, we assumed a Normal prior with location (mean) of 0 and scale (standard devation) of 6 for \(\beta_1\).

Conditional on the data, we estimate that for every 1 year increase in age, cholesterol increases by 0.32 mg/dl (95% credible interval 0.04 to 0.60).

1 Query “Explain how a slope from simple linear regression is interpreted using language a college graduate could understand. Provide a Bayesian and Frequentist interpretation.” VUMC aiChat tool, GPT-4. Retrieved 12/28/2023.

In simple linear regression, the slope (often denoted as “b” or “beta”) is interpreted as the expected change in the dependent (or response) variable for a one-unit increase in the independent (or predictor) variable, assuming all other variables are held constant.

From a Frequentist perspective, the slope is considered a fixed but unknown value which is estimated from the sample data. If the slope is found to be 2, for instance, it would suggest that for every one-unit increase in our predictor variable, we expect, on average, a 2-unit increase in the response variable. This is based on the data at hand and is subject to sampling variability. Confidence intervals can be constructed around this estimate to provide a range of plausible values for this unknown fixed parameter. If a 95% confidence interval for the slope is (1.5, 2.5), it would suggest that we are 95% confident that the true slope falls within this range.

In contrast, a Bayesian approach treats the slope as a random variable. Rather than a single fixed value, the slope has a distribution of possible values. This distribution combines our prior beliefs about what the slope might be (prior distribution) and the observed data (likelihood). The resulting distribution (posterior distribution) reflects our updated belief about the slope after seeing the data. If the mean of the posterior distribution is 2, it suggests that, given the prior and the data, our best guess is that a one-unit increase in the predictor variable corresponds to a 2-unit increase in the response variable on average. A credible interval, say a 95% credible interval of (1.5, 2.5), suggests that there is a 95% probability that the true value of the slope falls within this range, given our prior and the observed data.

When to use Bayesian or frequentist approaches to estimation2

On many occasions, if one is careful in execution, both approaches to analysis will yield essentially equivalent inference

For small sample sizes, Bayesian approaches with carefully considered priors are often the only way to go because it is difficult to obtain well-calibrated frequentist intervals

For medium to large samples, unless there is strong prior information that one wants to incorporate, robust frequentist estimation using sandwich estimation is very appealing because its consistency is guaranteed under mild conditions

For highly complex models, a Bayesian approach is often the most convenient way to formulate the model, and computation under the Bayesian approach is the most straightforward

In summary, in many instances carefully considered Bayesian and frequentist approach will lead to similar scientific conclusions. My goal is describe the advantages and shortcoming of each approach, but a strong recommendation of one over the other is not given as there is often no reason for stating a preference.

2 Wakefield, Jon. Bayesian and Frequentist Regression Methods. Section 1.6, Executive Summary

Borrowing information

Use other groups to make estimates in groups with sparse data

Intuitively, 67 and 69 year olds would provide some relevant information about 68 year olds

Assuming a straight line relationship tells us about other, even more distant, individuals

If we do not want to assume a straight line, we may only want to borrow information from nearby groups

Locally weighted scatterplot smooth line (lowess) added to the previous figures

Splines discussed in future lectures

May not want to borrow too much information

Linear relationship is an assumption, with often low power to detect departures from linearity

Always avoid extrapolating beyond the range of the data (e.g. ages under 65 or over 100)

Defining “Contrasts”

Define a comparison across groups to use when answering scientific questions

If the straight line relationship holds, the slope is the difference in mean cholesterol levels between groups differing by 1 year in age

Do we want to assume that comparisons of 65 to 66 year old subjects are the same as comparisons of 95 to 96 year old subjects?

If a non-linear relationship, the slope is still the average difference in mean cholesterol levels between groups differing by 1 year in age

Slope is a (first order or linear) test for trend

Regression output provides

Estimates

Intercept: Estimated mean cholesterol when age is 0

Slope: Estimated average difference in average cholesterol for two groups differing by 1 year in age

Standard errors

Confidence intervals

P-values for testing

Intercept is zero (usually unimportant)

Slope is zero (test for linear trend in means)

(Frequentist) Interpretation

From linear regression analysis, we estimate that for each year difference in age, the difference in mean cholesterol is 0.32 mg/dL. A 95% confidence interval (CI) suggests that this observation is not unusual if the true difference in mean cholesterol per year difference in age were between 0.05 and 0.59 mg/dL. Because \(p = 0.02\), we reject the null hypothesis that there is no linear trend in the average cholesterol across age groups using a significance level, \(\alpha\), of \(0.05\).

Response

The distribution of this variable will be compared across groups

Linear regression models the mean of the response variable

Log transformation of the response corresponds to modeling the geometric mean

Notation: It is extremely common to use \(Y\) to denote the response variable when discussing general methods

Predictor

Group membership is measured by this variable

Notation

When not using mnemonics, will be referred to as the \(X\) variable in simple linear regression (linear regression with one predictor)

Later, when we discuss multiple regression, will refer to \(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_p\) when there are up to \(p\) predictors

Regression Model

We typically consider a “linear predictor function” that is linear in the modeled predictors

Expected value (i.e. mean) of \(Y\) for a particular value of \(X\)

\(E[Y | X] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times X\)

In a deterministic world, a line is of the form \(y = mx + b\)

With no variation in the data, each value of \(y\) would like exactly on a straight line

Intercept \(b\) is values of \(y\) when \(x = 0\)

Slope \(m\) is the difference in \(y\) for a one unit difference in \(x\)

Statistics in not completely deterministic. The real world has variability

Response within groups is variable (people born on the same day will have different cholesterol levels!)

Randomness due to other variables impacting cholesterol

Inherent randomness

The regression line thus describes the central tendency of the data in a scatterplot of the response versus the predictor

Interpretation of regression parameters

Intercept \(\beta_0\): Mean \(Y\) for a group with \(X=0\)

Often \(\beta_0\) is not of scientific interest

May be out of the range of data, or even impossible to observe \(X=0\)

Slope \(\beta_1\): Difference in mean \(Y\) across groups differing in \(X\) by 1 unit

Usually measures association between \(Y\) and \(X\)

\(E[Y | X] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times X\)

Derivation of interpretation

Simple linear regression of response \(Y\) on predictor \(X\)

Mean of any arbitrary group can be derived from the equation \[ Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i \]

Interpretation determined by considering possible values of \(X\)

Model: \(E[Y_i | X_i] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times X_i\)

When \(X_i = 0\), \(E[Y_i | X_i = 0 ] = \beta_0\)

When \(X_i = x\), \(E[Y_i | X_i = x ] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x\)

When \(X_i = x + 1\), \(E[Y_i | X_i = x + 1 ] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \beta_1\)

We can use the above to get an equation for \(\beta_1\)

\[ E[Y_i | X_i = x + 1 ] - E[Y_i | X_i = x ] = \\ (\beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \beta_1) - (\beta_0 + \beta_1 x) \\ = \beta_1 \]

Using scalars, the simple linear regression model can be written as

\(Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times X_i + \epsilon_i\)

\(i = 1, \ldots, n\)

\(i\) indexes the independent sampling units (e.g. subjects)

\(n\) is the total number of independent sampling units

This formulauation drops the expected value notation, add in \(\epsilon_i\)

\(\epsilon_i\) are the “Residuals” or “Errors”

\(E[\epsilon_i] = 0\)

\(V[\epsilon_i] = \sigma^2\) (constant variance assumption)

\({\boldsymbol{Y}}= \left( \begin{array}{c} Y_1 \\ Y_2 \\ \vdots \\ Y_n \end{array} \right)_{n\times1}\) \({\boldsymbol{X}}= \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & x_1 \\ 1 & x_2 \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_n \end{array} \right)_{n\times2}\) \({\boldsymbol{\beta}}= \left( \begin{array}{c} \beta_0 \\ \beta_1 \\ \end{array} \right)_{2\times1}\) \({\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}= \left( \begin{array}{c} \epsilon_1 \\ \epsilon_2 \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_n \end{array} \right)_{n\times1}\)

\(E[{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}] = {\boldsymbol{0}}\), where \({\boldsymbol{0}}= \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ \vdots \\0 \end{array} \right)_{n\times1}\)

\(V[{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}] = \sigma^2 {\boldsymbol{I}}\), where \({\boldsymbol{I}}= \left( \begin{array}{cccc} 1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \ldots & 1 \end{array} \right)_{n\times n}\)

\(E[{\boldsymbol{Y}}] = {\boldsymbol{X}}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\)

I am using standard notation to indicate matrices/vectors and scalars

Boldface indicates a vector or matrix (\({\boldsymbol{Y}}\), \({\boldsymbol{X}}\), \({\boldsymbol{\beta}}\), \({\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\), \({\boldsymbol{0}}\), \({\boldsymbol{I}}\))

Normal typeface indicates a scalar (\(Y_i\), \(x_i\), \(\beta_0\), \(\beta_1\), \(\epsilon_i\), \(0\), \(1\))

Example analysis conducted in class involving BMI (response) with gender (predictor 1) and age (predictor 2)

This is “Lab 1” and will serve as an example of how future labs will proceed

Often linear regression models are specified in terms of the response instead of the mean response

Include an error term in the model, \(\epsilon_i\)

Model \(Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i + \epsilon_i\)

The linear regression model is divided into two parts

The mean, or systematic, part (the “signal”)

The error, or random, part (the “noise”)

Residuals

\(\hat{\epsilon}_i = Y_i - \left(\hat{\beta_0} + \hat{\beta_1} X_i\right)\)

\(\hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} = {\boldsymbol{Y}}- {\boldsymbol{X}}\hat{{\boldsymbol{\beta}}}\)

\(\hat{{\boldsymbol{\beta}}} = \left({\boldsymbol{X}}'{\boldsymbol{X}}\right)^{-1} \left({\boldsymbol{X}}'{\boldsymbol{Y}}\right)\)

The mean of the residuals is \(0\)

The standard deviation of the residuals is the “Root Mean Square Error”

In our example analysis of BMI and gender, the RMSE is exactly equal to the pooled estimate of the standard deviation from a two-sample, equal variance t-test

In our example analysis of BMI and age, the RMSE is the square root of the average variances across the age groups

In many textbooks, \(\epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\)

A common \(\sigma^2\) implies constant variance across all levels of the grouping variable, “homoscedasticity”

Normality of the residuals is a nice property, but it is not necessary (and rarely observed in practice)

We will discuss how lack of Normality and heteroscedasticity impact statistical inference

Most common uses of regression

Prediction: Estimating what a future value of \(Y\) will be based on observed \(X\)

Comparisons within groups: Describing the distribution of \(Y\) across levels of the grouping variable \(X\) by estimating the mean \(E[Y | X]\)

Comparisons across groups: Differences appear across groups if the regression parameter slope estimate \(\beta_1\) is non-zero

Valid statistical inference (CIs, p-values) about associations requires three general assumptions

Assumption 1: Approximately Normal distributions for the parameter estimates

Normal data or “large” N

It is often surprising how small “large” can be

Definition of large depends on the error distribution and relative sample sizes within each group

With exactly Normally distributed errors, only need one observation (or two to estimate a slope)

With very heavy tails, “large” can be very large

See Lumley, et al., Ann Rev Pub Hlth, 2002

Assumption 2: Independence of observations

Classic regression: Independence of all observation (now)

Robust standard errors: Correlated observations within identified clusters (later)

Assumption 3: Assumption about the variance of observations within groups

Classic regression: Homoscedasticity (equal variance across groups)

Robust standard errors: Allows for unequal variance across groups

Note that some textbooks will claim there are more than three assumptions. In truth, additional assumptions are not needed to make the aforementioned statistical inference about associations. However …

Valid statistical inference (CIs, p-values) about mean responses in specific groups requires a further assumption

Assumption 4: Adequacy of the linear model

If we are trying to borrow information about the mean from neighboring groups, and we are assuming a straight line relationship, the straight line needs to be true

No longer saying there is just a linear trend in the means, but now need to believe that all the means lie on a straight line

Note that we can model transformations of the measured predictor

For inference about individual observations (prediction intervals, P-values) in specific groups requires another assumption

Assumption 5: Assumptions about the distribution of the errors within each group (a very strong assumption)

Classically: Errors have the same Normal distribution within each grouping variable

Robust standard error will not help

Prediction intervals assume a common error distribution across groups (homoscedasticity)

Possible extension: Errors have the same distribution, but not necessarily Normal (rarely implemented in frequentist software)

Bootstrapping

Bayesian analysis

Other flexible approaches

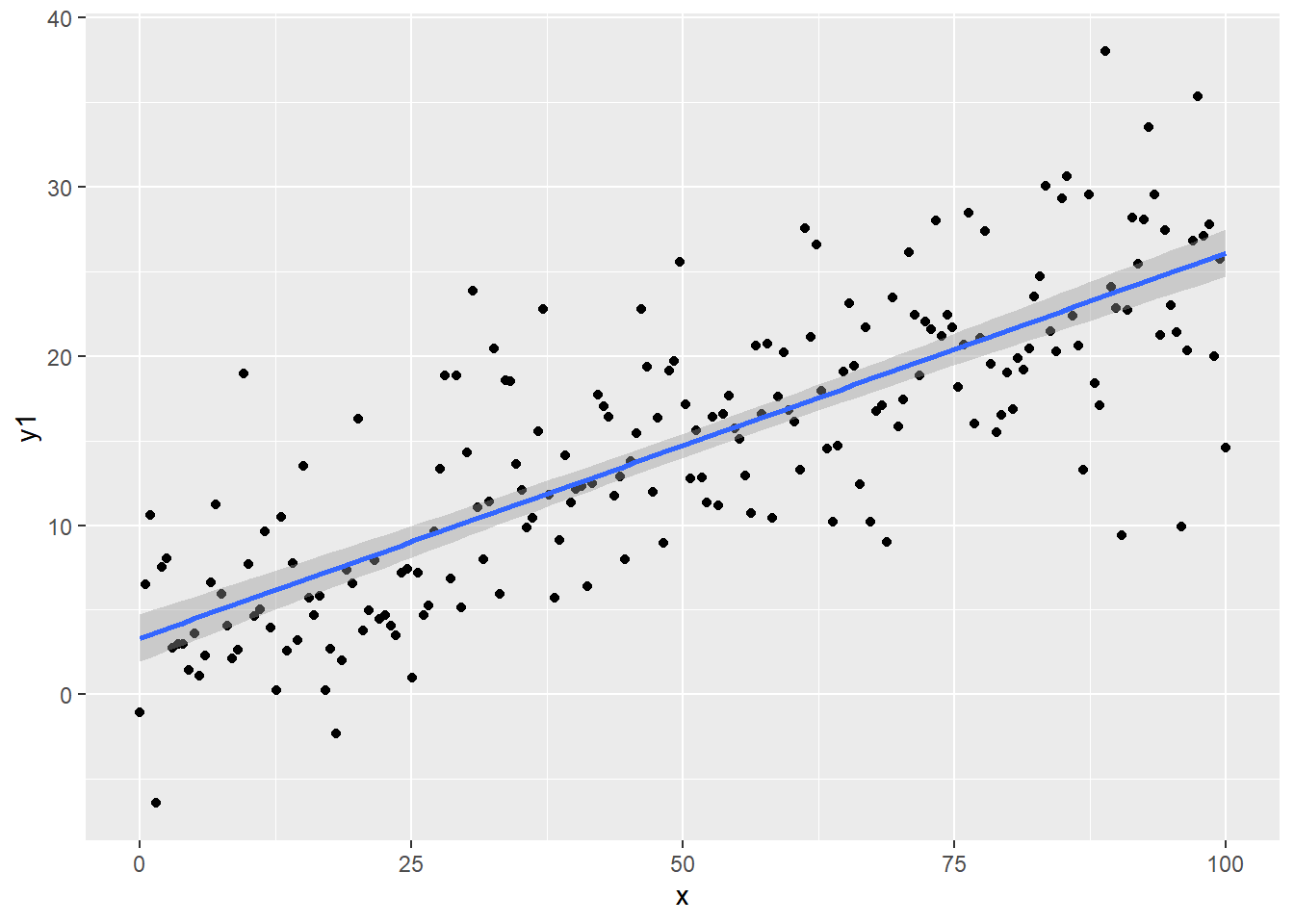

set.seed(1234)

n <- 200

regassumptions <- data.frame(x=seq(from=0, to=100, length=n))

# Linear model correct, Normal errors

regassumptions$y1 <- 5 + 0.2*regassumptions$x + rnorm(n,0,5)

# Linear model correct, Skewed errors

regassumptions$y2 <- 5 + 0.2*regassumptions$x + rlnorm(n,0,1)

# Linear model correct, errors increasing with predictor (so increasing with Y too)

regassumptions$y3 <- 5 + 0.2*regassumptions$x + rnorm(n,0,1+regassumptions$x*.1)

# Linear model incorrect, Normal error

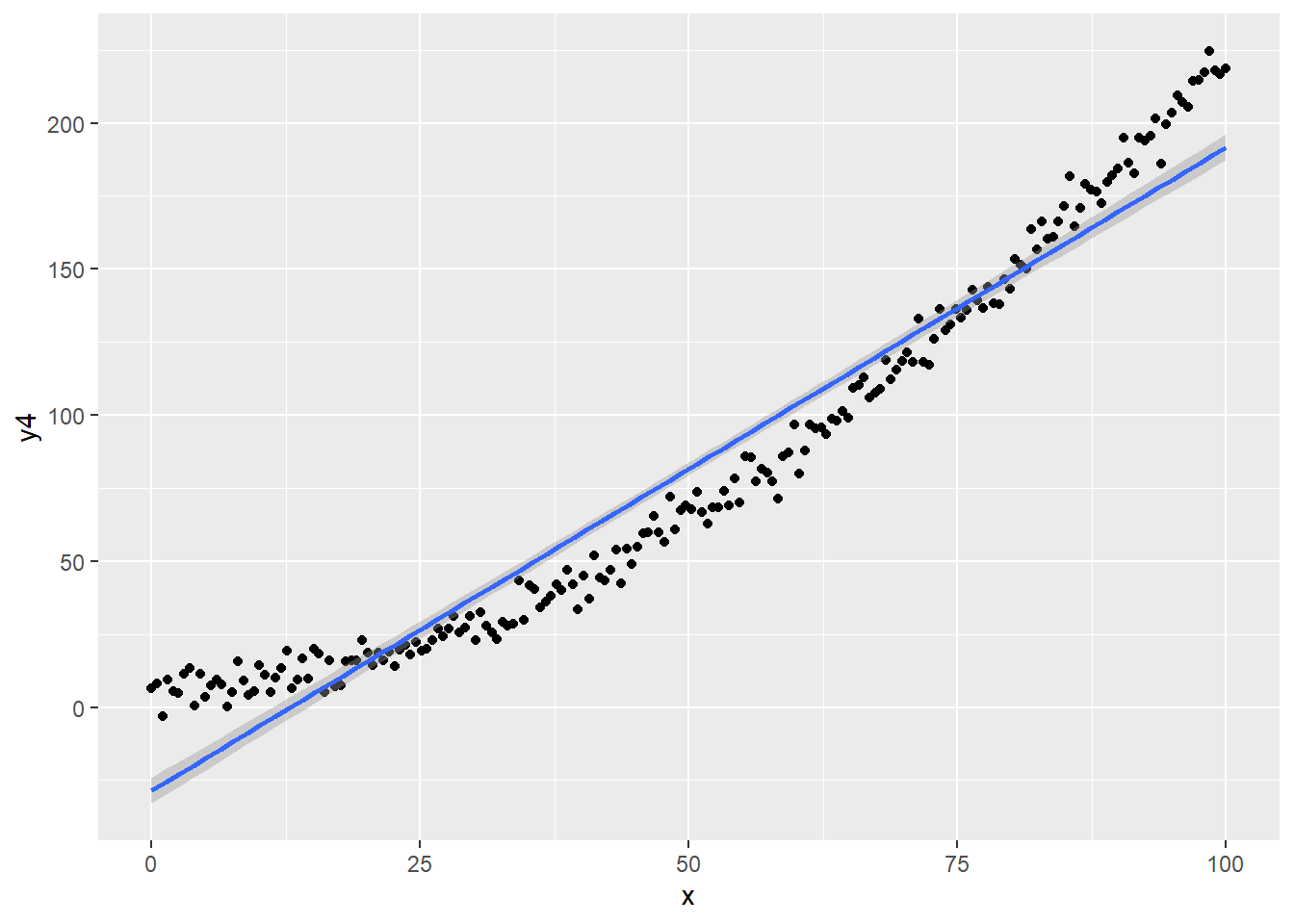

regassumptions$y4<- 5 + 0.2*regassumptions$x + 0.02*(regassumptions$x)^2 + rnorm(n,0,5)

ggplot(regassumptions, aes(x=x, y=y1)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(method="lm")

model.y1 <- lm(y1 ~ x, data = regassumptions)

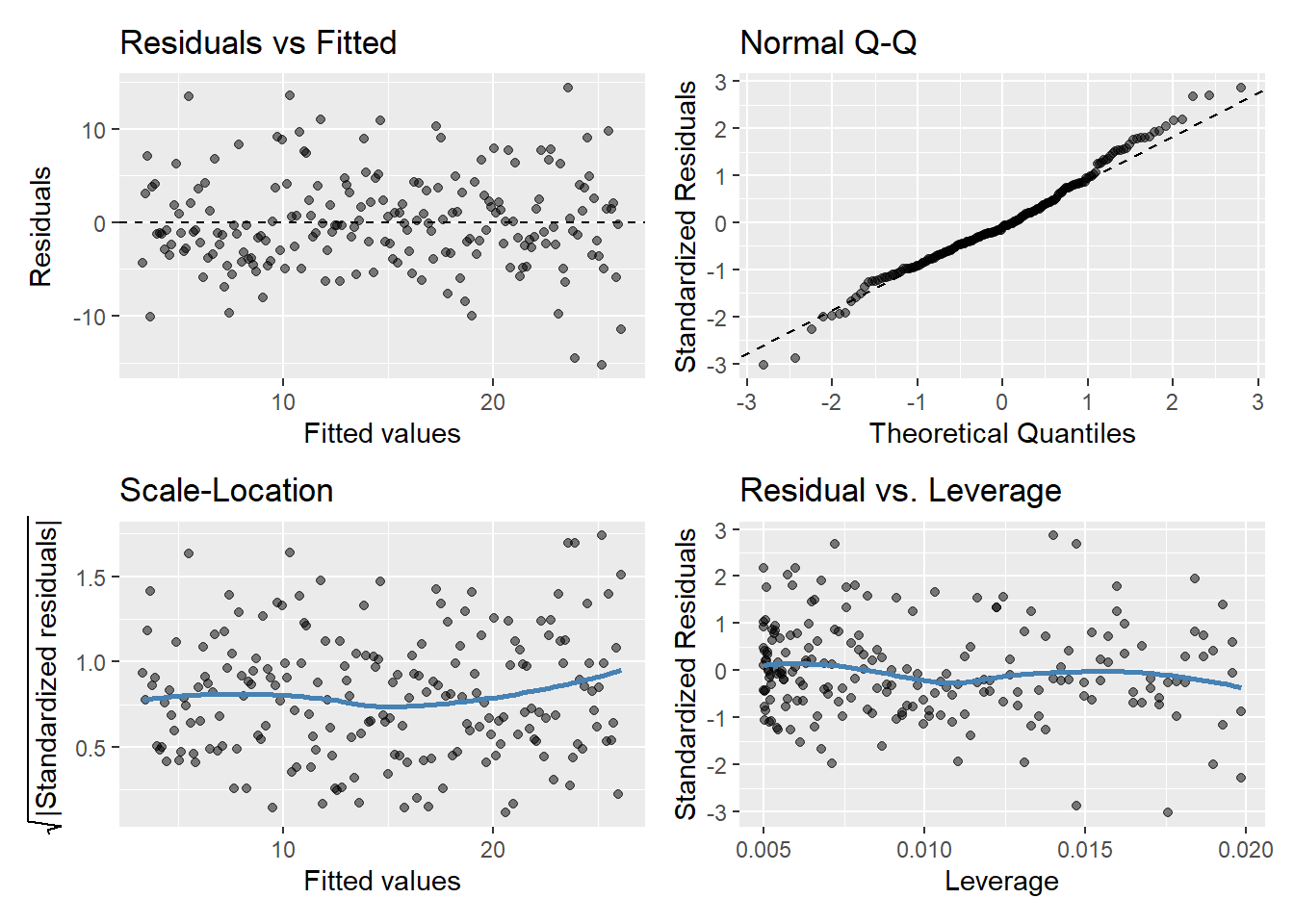

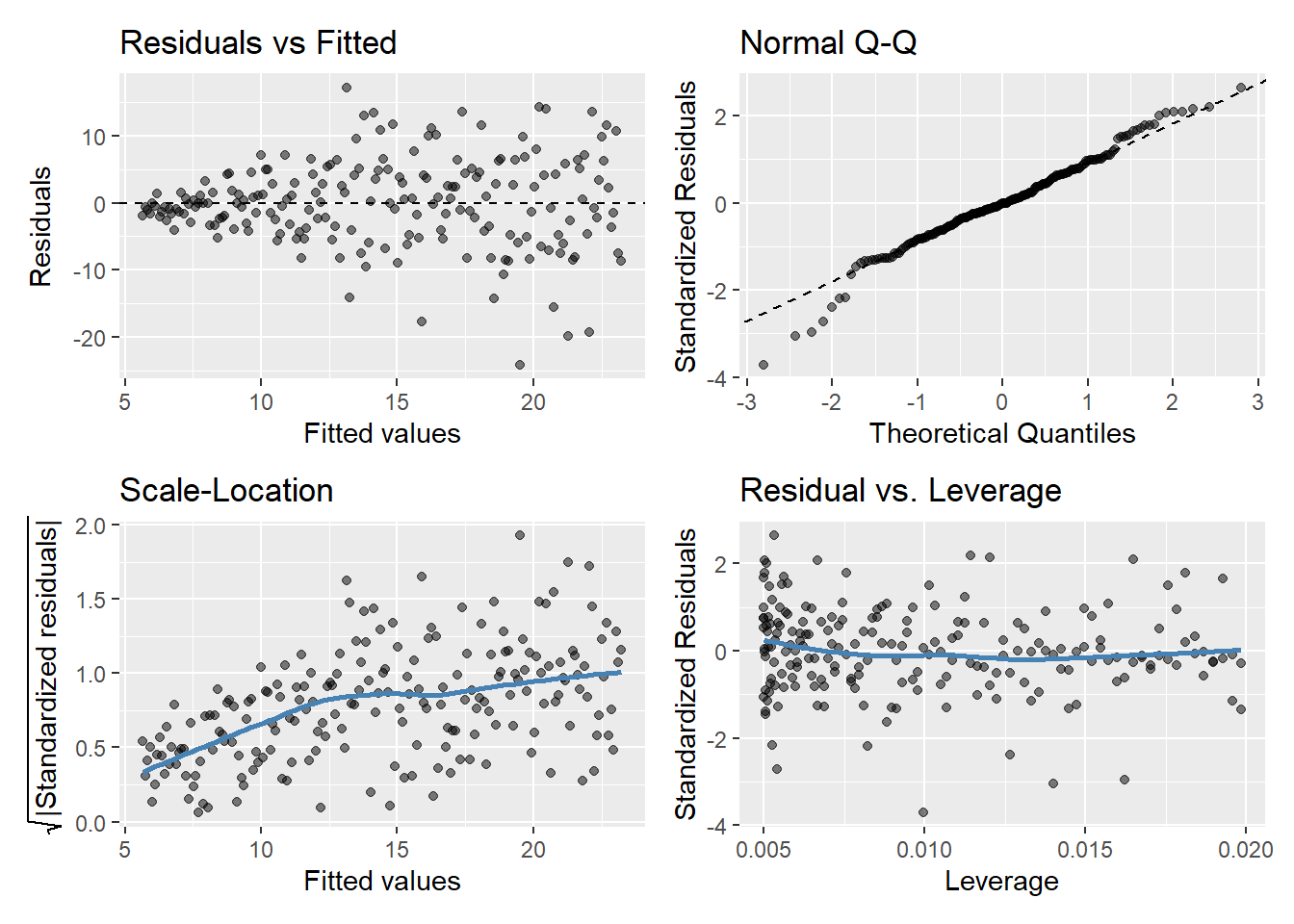

gglm(model.y1)

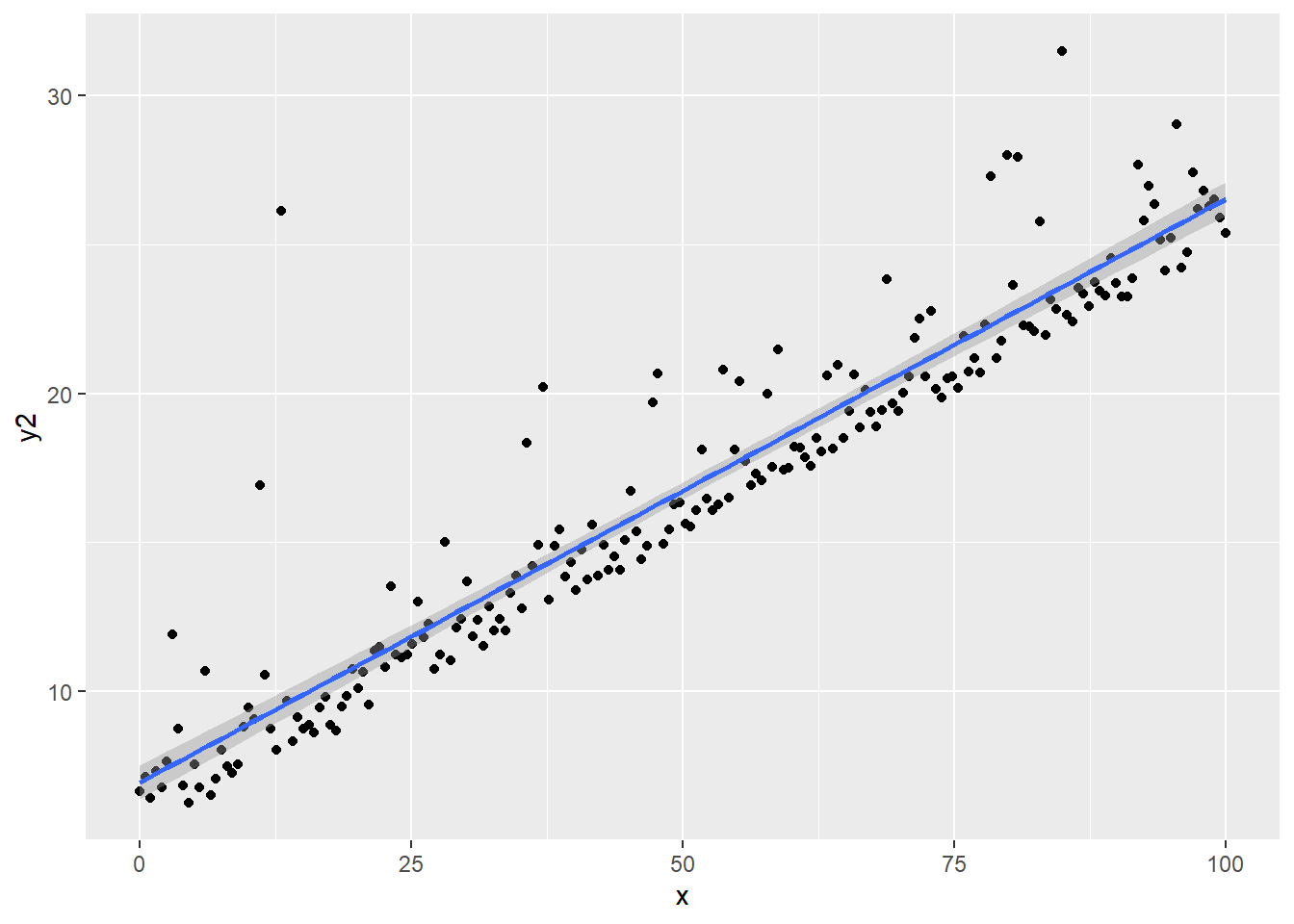

ggplot(regassumptions, aes(x=x, y=y2)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(method="lm")

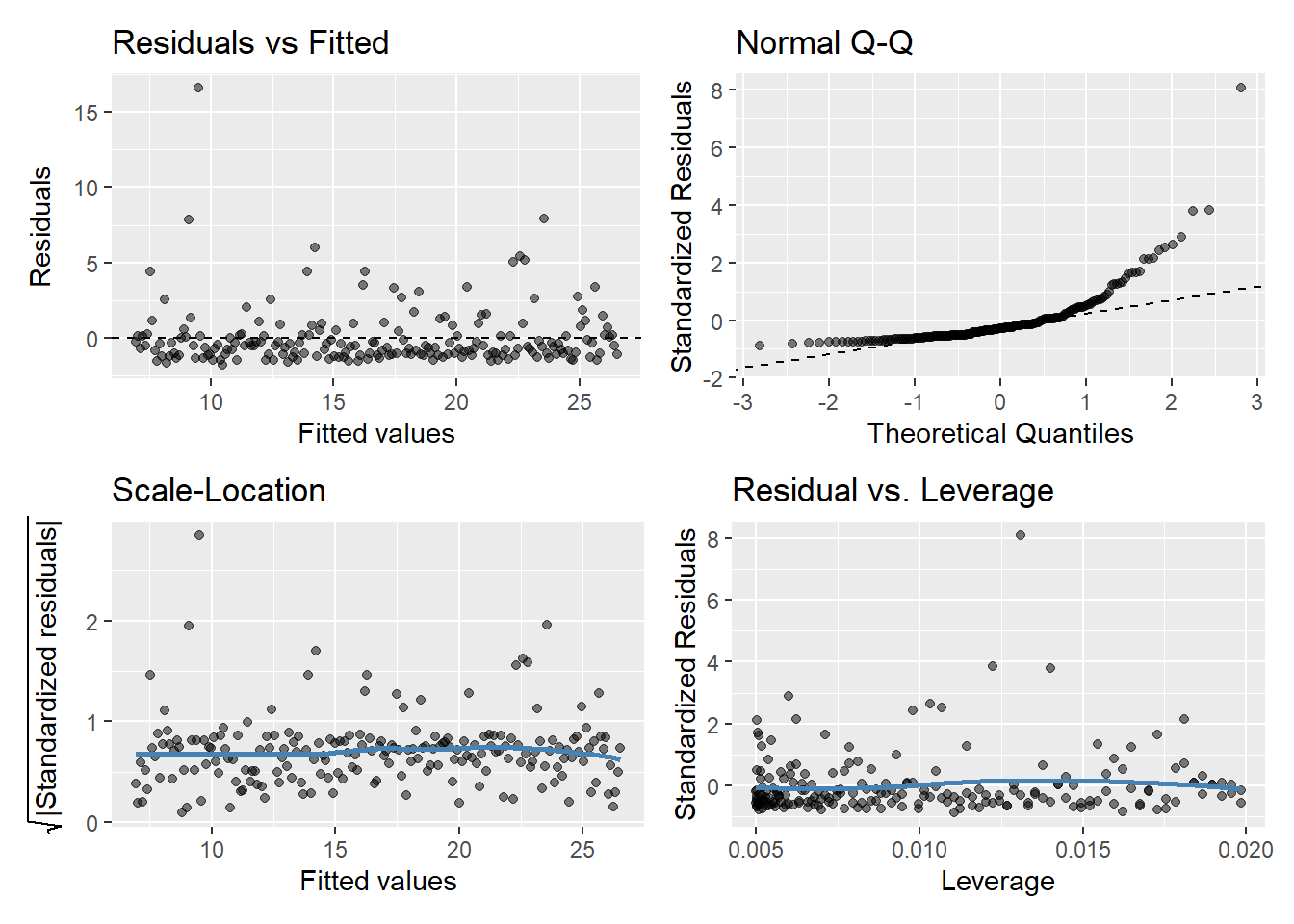

model.y2 <- lm(y2 ~ x, data = regassumptions)

gglm(model.y2)

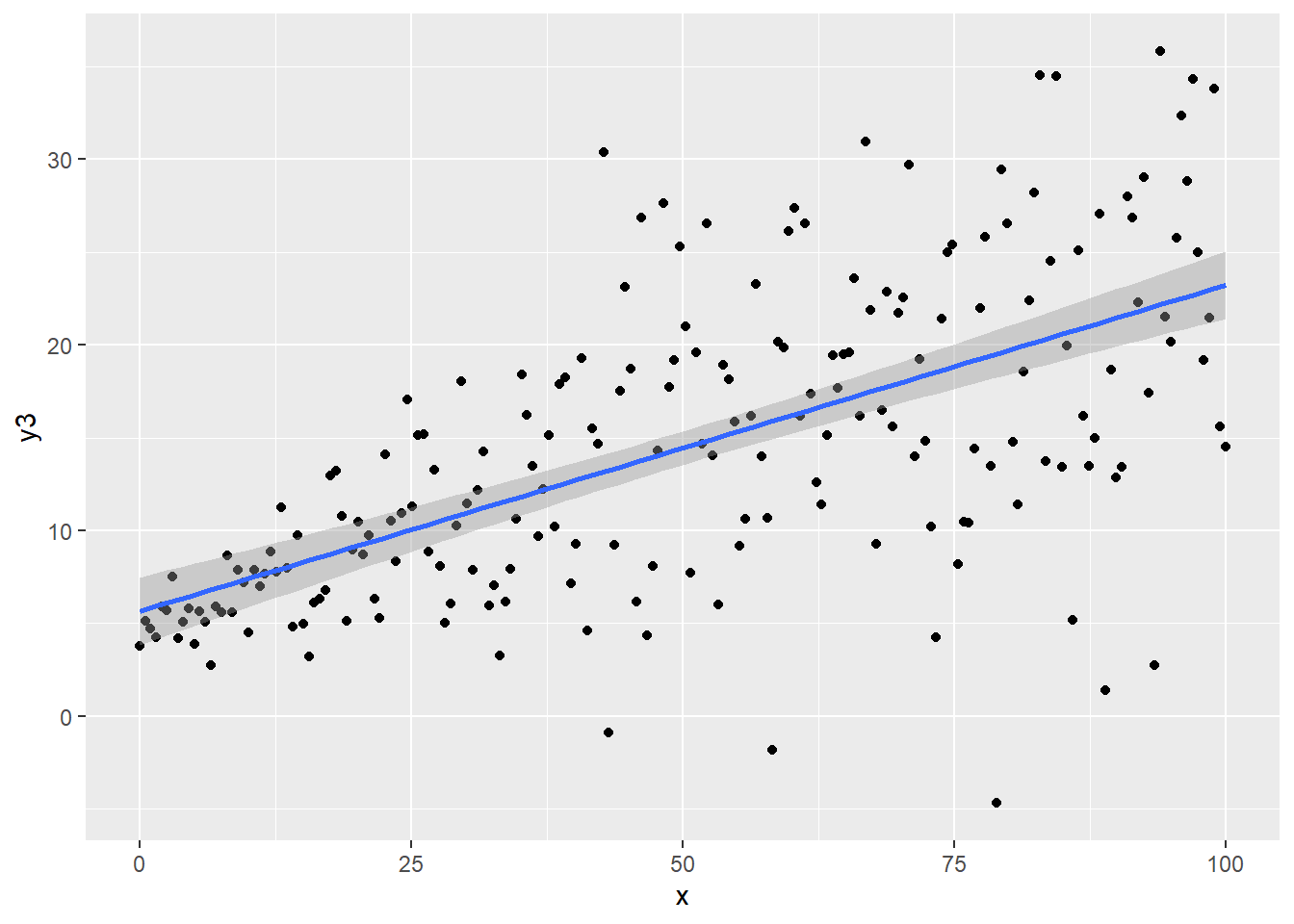

ggplot(regassumptions, aes(x=x, y=y3)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(method="lm")

model.y3 <- lm(y3 ~ x, data = regassumptions)

gglm(model.y3)

ggplot(regassumptions, aes(x=x, y=y4)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(method="lm")

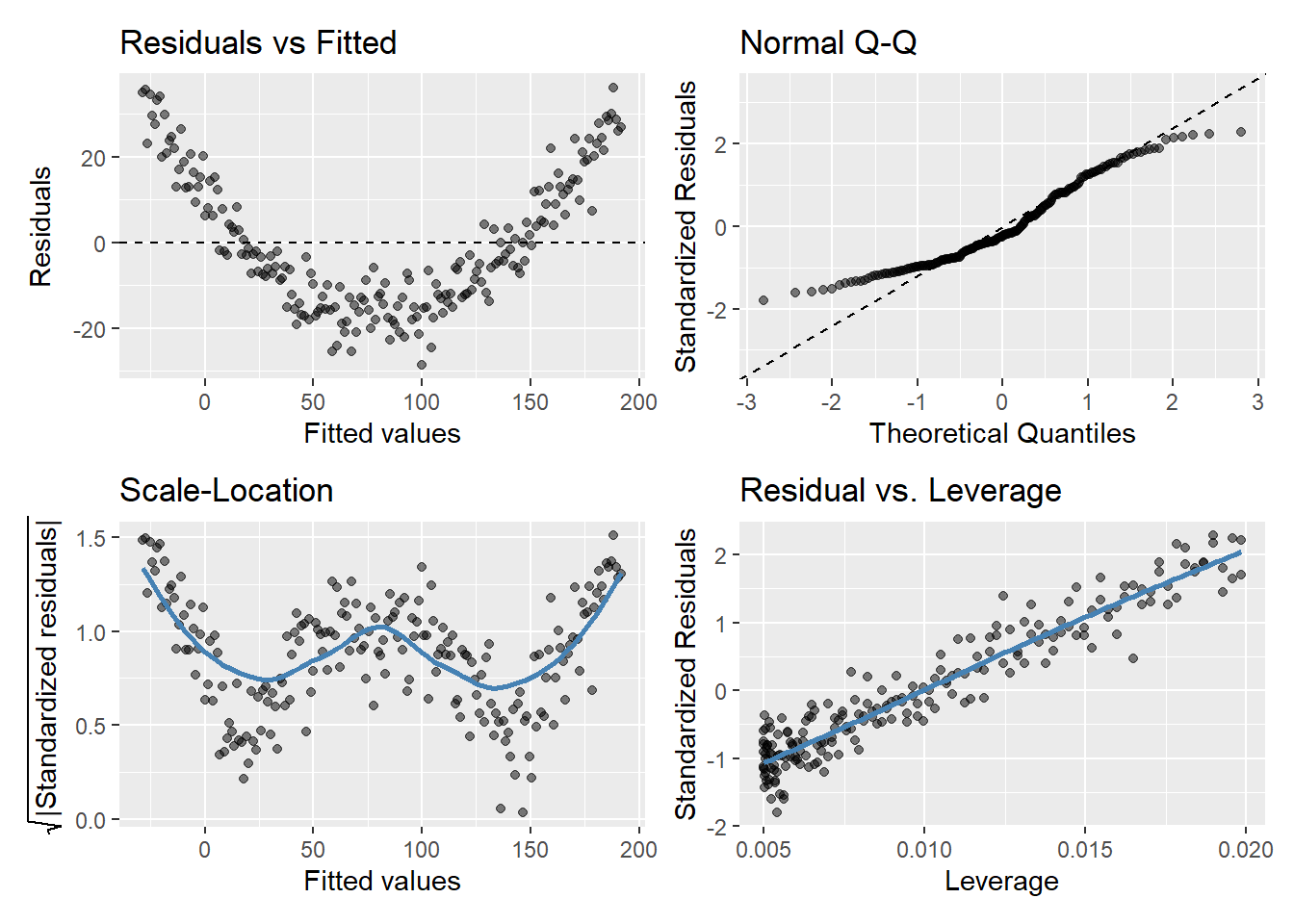

model.y4 <- lm(y4 ~ x, data = regassumptions)

gglm(model.y4)

Regression based inference about associations is far more trustworthy than estimation of group means or individual predictions.

There is much to be gained by using robust variance estimates

| Linearity | Homoskedasticity | Normality |

|---|---|---|

| Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | N |

| Y | N | Y |

| Y | N | N |

| N | Y | Y |

| N | Y | N |

| N | N | Y |

| N | N | N |

| \(\hat{\beta}\) | \(\hat{\textrm {Var}}_{NR}(\hat{\beta})\) | \(\hat{\textrm{ Var}}_R(\hat{\beta})\) |

|---|---|---|

| Y | Y | Y |

| Y | M2 | M2 |

| Y | N | Y |

| Y | N | M2 |

| M1 | N | M3 |

| M1 | N | M2,3 |

| M1 | N | M2 |

| M1 | N | M2,3 |

Slope is statistically different from 0 using robust standard errors

Observed data is atypical of a setting with no linear trend in mean response across groups

Data suggests evidence of a trend toward larger (or smaller) means in groups having larger values of the predictor

(To the extent the data appears linear, estimates of the group means will be reliable)

Many possible reasons why the slope is not statistically different from 0 using robust standard errors

There may be no association between the response and predictor

There may be an association, but not in the parameter considered (the mean response)

There may be an association in the parameter considered, but the best fitting line has zero slope

There may be a first order trend in the parameter considered, but we lacked the precision to be confident that it truly exists (a type II error)

Much statistical literature has been devoted to methods for checking the assumptions for regression models

My philosophy: Model checking is generally fraught with peril as it necessarily involves multiple comparisons

We cannot reliably use the sampled data to assess whether it accurately portrays the population

We are more worried about the data from the population that we might not have sampled

It is not so much the abnormal points that we see, but the ones that are hiding in the population that will make our model perform badly

But, do tend to worry more when we see a tendency to extreme outliers in the sample or clear departures from model assumptions

If we over-check our model and make adjustments to the model based on our observed data, we will inflate the type I error rate (i.e. will be more likely to claim statistical significance when it doesn’t really exist). We run the risk of creating a model that fits our data well but does not generalize.

Estimates are biased away from the null

Reported standard errors are too small

If we fish through the data, we will always find significant results

In clinical trials, often Phase II results are not able to be replicated in Phase III trials

Instead of extensive model checking, go back to our choices of inference when planning our analysis

Best to plan for unusual data

There is often little to be lost and much to be gained by using the robust standard error estimates

By using robust errors, avoids much of the need for model checking

Model checking is almost entirely data driven

Robust standard errors is a more logical scientific approach

Minimize the need to presume more knowledge than the question we are trying to answer

E.g., if we don’t know how the means might differ, why should we presume to know how the variances or the shape of the distribution might behave?

Plot of \(\hat{\epsilon_i}\) versus \(\hat{y_i}\)

If assumptions hold, should be a random pattern about zero. See Figure 5 for example.

If you have a priori concerns about non-constant variance, this is one potential check

The scale-location plot is very similar to residuals vs fitted values, and is used to evaluate the homoskedasticity assumption

It uses the square root of the absolute value of standardized residuals instead of plotting the residuals themselves

We want to check two things

That the best fit line is approximately horizontal. If it is, then the average magnitude of the standardized residuals isn’t changing much as a function of the fitted values.

That the spread around the fit line doesn’t vary with the fitted values. If so, then the variability of magnitudes doesn’t vary much as a function of the fitted values.

Used to evaluate Normality of the residuals

Plot of standardized residuals versus theoretical quantities from a N(0,1) distribution

If assumptions hold, the standardized residuals should be a random sample from a N(0,1) distribution

We can use quantiles of the Normal distribution to check how closely the observed matches the expected

Similar idea would be a histogram or density plot of the (standardized) residuals that could be visually evaluated for Normality

Used to check for outliers

Plot can help us to identify influential observations, if there are any

Influence differs from leverage. Not all outliers influence the regression coefficient estimates

There are several libraries available in R for fitting models with robust error estimates

There are also several different flavors of robust estimators

For now, we are going to consider the default “Huber-White sandwich estimator”

In Stata, the Huber-White robust estimate of the standard error can be obtained using the ‘robust’ option

regress chol age, robustIn the following examples I provide estimates using classical linear regression and linear regression estimate using robust standard errors. For each of these example compare

Estimates of the intercept, \(\hat{\beta_0}\)

Estimates of the slope, \(\hat{\beta_1}\)

Estimates of the standard errors, \(\hat{\textrm{se}}(\hat{\beta_0})\) and \(\hat{\textrm{se}}(\hat{\beta_1})\)

fit.ols <- ols(chol ~ age, data=plotdata, x=TRUE)

fit.olsLinear Regression Model

ols(formula = chol ~ age, data = plotdata, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 301 LR chi2 5.43 R2 0.018

sigma15.3405 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.015

d.f. 299 Pr(> chi2) 0.0198 g 2.344

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-39.591 -10.524 -0.234 11.154 41.819

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 203.2259 10.3138 19.70 <0.0001

age 0.3209 0.1375 2.33 0.0203 robcov(fit.ols)Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = chol ~ age, data = plotdata, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 301 LR chi2 5.43 R2 0.018

sigma15.3405 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.015

d.f. 299 Pr(> chi2) 0.0198 g 2.344

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-39.591 -10.524 -0.234 11.154 41.819

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 203.2259 10.3790 19.58 <0.0001

age 0.3209 0.1378 2.33 0.0205 ols(y1 ~ x, data=regassumptions, x=TRUE)Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = y1 ~ x, data = regassumptions, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 200 LR chi2 200.34 R2 0.633

sigma5.0531 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.631

d.f. 198 Pr(> chi2) 0.0000 g 7.659

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-15.2533 -3.2042 -0.4963 3.0693 14.4377

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 3.3375 0.7119 4.69 <0.0001

x 0.2275 0.0123 18.47 <0.0001 robcov(ols(y1 ~ x, data=regassumptions, x=TRUE))Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = y1 ~ x, data = regassumptions, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 200 LR chi2 200.34 R2 0.633

sigma5.0531 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.631

d.f. 198 Pr(> chi2) 0.0000 g 7.659

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-15.2533 -3.2042 -0.4963 3.0693 14.4377

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 3.3375 0.7002 4.77 <0.0001

x 0.2275 0.0132 17.20 <0.0001 ols(y3 ~ x, data=regassumptions, x=TRUE)Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = y3 ~ x, data = regassumptions, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 200 LR chi2 95.93 R2 0.381

sigma6.5232 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.378

d.f. 198 Pr(> chi2) 0.0000 g 5.909

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-24.1947 -3.7861 -0.1145 4.1816 17.2286

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 5.6640 0.9191 6.16 <0.0001

x 0.1755 0.0159 11.04 <0.0001 robcov(ols(y3 ~ x, data=regassumptions, x=TRUE))Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = y3 ~ x, data = regassumptions, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 200 LR chi2 95.93 R2 0.381

sigma6.5232 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.378

d.f. 198 Pr(> chi2) 0.0000 g 5.909

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-24.1947 -3.7861 -0.1145 4.1816 17.2286

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 5.6640 0.5955 9.51 <0.0001

x 0.1755 0.0153 11.49 <0.0001 ols(y2 ~ x, data=regassumptions, x=TRUE)Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = y2 ~ x, data = regassumptions, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 200 LR chi2 431.83 R2 0.885

sigma2.0635 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.884

d.f. 198 Pr(> chi2) 0.0000 g 6.596

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.8206 -1.1341 -0.6103 0.1731 16.6448

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 6.9339 0.2907 23.85 <0.0001

x 0.1959 0.0050 38.95 <0.0001 robcov(ols(y2 ~ x, data=regassumptions, x=TRUE))Linear Regression Model

ols(formula = y2 ~ x, data = regassumptions, x = TRUE)

Model Likelihood Discrimination

Ratio Test Indexes

Obs 200 LR chi2 431.83 R2 0.885

sigma2.0635 d.f. 1 R2 adj 0.884

d.f. 198 Pr(> chi2) 0.0000 g 6.596

Residuals

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.8206 -1.1341 -0.6103 0.1731 16.6448

Coef S.E. t Pr(>|t|)

Intercept 6.9339 0.3526 19.67 <0.0001

x 0.1959 0.0056 35.18 <0.0001 Notation

\(\rho\) signifies the population value

\(r\) (or \(\hat{\rho}\)) is the estimated correlation from data

Formula

\(r = \frac{\Sigma(x_i - \bar{x})(y_i - \bar{y})}{\sqrt{\Sigma(x_i - \bar{x})^2\Sigma(y_i - \bar{y})^2}}\)

Range: \(-1 \leq r \leq 1\)

Interpretation

Measures the linear relationship between \(X\) and \(Y\)

Correlation coefficient is a unitless index of strength of association between two variables (+ = positive association, - = negative, 0 = no association)

Can test for significant association by testing whether the population correlation is zero t = which is identical to the \(t\)-test used to test whether the population \(r\) is zero; \(\textrm{d.f.} = n-2\)

Use probability calculator for \(t\) distribution to get a 2-tailed \(P\)-value

Confidence intervals for population \(r\) calculated using Fisher’s \(Z\) transformation

\[Z = \frac{1}{2} \textrm{log}_\textrm{e} \left( \frac{1+r}{1-r} \right)\]

For large \(n\), \(Z\) follows a Normal distribution with standard error \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{n-3}}\)

To calculate a confidence interval for \(r\), first find the confidence interval for \(Z\) then transform back to the \(r\) scale

\[\begin{aligned} Z & = & \frac{1}{2} \textrm{log}_\textrm{e} \left( \frac{1+r}{1-r} \right) \\ 2*Z & = & \textrm{log}_\textrm{e} \left( \frac{1+r}{1-r} \right) \\ \textrm{exp}(2*Z) & = & \left( \frac{1+r}{1-r} \right) \\ \textrm{exp}(2*Z) * (1-r) & = & 1 + r \\ \textrm{exp}(2*Z) - r * \textrm{exp}(2*Z) & = & 1 + r \\ \textrm{exp}(2*Z) - 1 & = & r * \textrm{exp}(2*Z) + r \\ \textrm{exp}(2*Z) - 1 & = & r \left(\textrm{exp}(2*Z) + 1\right) \\ \frac{\textrm{exp}(2*Z) - 1}{\textrm{exp}(2*Z) + 1} & = & r \\ \end{aligned}\]

Example (Altman 89-90): Pearson’s \(r\) for a study investigating the association of basal metabolic rate with total energy expenditure was calculated to be \(0.7283\) in a study of \(13\) women. Derive a 95% confidence interval for \(r\)

\[Z = \frac{1}{2} \textrm{log}_\textrm{e} \left( \frac{1+r}{1-r} \right) = 0.9251\]

The lower limit of a 95% CI for \(Z\) is given by \(0.9251 + 1.96*\frac{1}{\sqrt{n-3}} = 0.3053\)

The upper limit is \(0.9251 + 1.96*\frac{1}{\sqrt{n-3}} = 1.545\)

A 95% CI for the population correlation coefficient is given by transforming these limits from the \(Z\) scale back to the \(r\) scale.

\[\frac{\textrm{exp}(2*0.3053) - 1}{\textrm{exp}(2*0.3053) + 1} \hspace{.5cm} \textrm{to} \hspace{.5cm} \frac{\textrm{exp}(2*1.545) - 1}{\textrm{exp}(2*1.545) + 1}\]

fisher.z <- function(r) {.5 * log((1+r)/(1-r))}

fisher.z.inv <- function(z) {(exp(2*z)-1) / (exp(2*z)+1)}

fisher.z.se <- function(n) {1/sqrt(n-3)}

fisher.z.inv(fisher.z(0.7283)) #Should be original value[1] 0.7283fisher.z(0.7283)[1] 0.9250975fisher.z(0.7283)-1.96*fisher.z.se(13)[1] 0.3052911fisher.z(0.7283)+1.96*fisher.z.se(13)[1] 1.544904fisher.z.inv(fisher.z(0.7283)+c(-1.96, 1.96)*fisher.z.se(13))[1] 0.2961472 0.9129407Pearson’s correlation (\(\rho\)) is directly related to linear regression

Correlation treats \(Y\) and \(X\) symmetrically, but we can relate

\(E[Y | X]\) as a function of \(X\)

\(E[Y | X] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X\)

\(\beta_1 = \rho \frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}\)

\(E[Y | X]\): mean \(Y\) withing groups having equal \(X\)

\(\beta_1\): difference in mean \(Y\) per 1 unit difference in \(X\)

\(\rho\): true correlation between \(Y\) and \(X\)

\(\sigma_Y\): standard deviation of \(Y\)

\(\sigma_X\): standard deviation of \(X\)

More interpretable formulation of \(\rho\)

\(\rho \approx \beta \sqrt{\frac{\textrm{Var}(X)}{\beta^2\textrm{Var}(X) + \textrm{Var}(Y | X = x)}}\)

\(\beta\): slope between \(Y\) and \(X\)

\(\textrm{Var}(X)\): variance of \(X\) in the sample

\(\textrm{Var}(Y | X = x)\): variance of \(Y\) in groups having the same value of \(X\) (the vertical spread of data)

Correlation tends to increase in absolute value as

The absolute value of the slope of the line increases

The variance of data decreases within groups that share a common value of \(X\)

The variance of \(X\) increases

Scientific uses of correlation

The slope between \(X\) and \(Y\) is of scientific interest

The variance of \(Y\) given \(X=x\) is partly of scientific interest, but can also be impacted by restricting sampling to certain values of another variable

The variance of height given age is less if sampling just males than if sampling both sexes

The variance of \(X\) is often set by study design (which is often not of scientific interest)

Hypothesis tests for a nonzero correlation are exactly the same as a test for a nonzero slope in classical linear regression

The statistical significance of a given value of \(\rho\) depends only on the sample size

Correlation is more of a statistical measure than a scientific measure

Geometric means of distributions are typically analyzed by using linear regression on the log transformed outcome

Used for inference under the following circumstances

We are (scientifically) interested in multiplicative rather than additive models

We want to down-weight the impact of outliers

The standard deviation of the response in a groups is proportional to the mean

Linear regression on the log transformed \(Y\)

Note that in statistics \(\textrm{log}\) almost always refers the the natural log (\(\textrm{log}_e\))

Model: \(E[\textrm{log} Y_i | X_i] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times X_i\)

When \(X_i = 0\): \(E[\textrm{log} Y_i | X_i = 0] = \beta_0\)

When \(X_i = x\): \(E[\textrm{log} Y_i | X_i = x] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times x\)

When \(X_i = x+1\): \(E[\textrm{log} Y_i | X_i = x + 1] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times x + \beta_1\)

Restate the model as log link for geometric mean

Model: \(\textrm{log GM}[Y_i | X_i] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times X_i\)

When \(X_i = 0\): \(\textrm{log GM}[Y_i | X_i = 0] = \beta_0\)

When \(X_i = x\): \(\textrm{log GM}[Y_i | X_i = x] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times x\)

When \(X_i = x+1\): \(\textrm{log GM}[Y_i | X_i = x + 1] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times x + \beta_1\)

Interpretation of parameters by back-transforming model

Model: \(\textrm{GM}[Y_i | X_i] = e^{\beta_0} \times e^{\beta_1 \times X_i}\)

When \(X_i = 0\): \(\textrm{GM}[Y_i | X_i = 0] = e^{\beta_0}\)

When \(X_i = x\): \(\textrm{GM}[Y_i | X_i = x] = e^{\beta_0} \times e^{\beta_1 \times x}\)

When \(X_i = x+1\): \(\textrm{GM}[Y_i | X_i = x + 1] = e^{\beta_0} \times e^{\beta_1 \times x} \times e^{\beta_1}\)

Question: How does FEV differ across height groups?

Scientific justification for summarizing with geometric mean

FEV is a volume

Height is a linear dimension

Each dimension of lung size is proportional to height

Standard deviation is likely proportional to height

Science: \(FEV \propto Height^3\) or \(\sqrt[3]{FEV} \propto Height\)

Statistics: \(\textrm{log}(FEV) \propto 3 \textrm{ log}(Height)\)

Statistical preference for (any) transformations of response

May transform to equal variance across groups

Homoscedasticity allows for easier inference

Statistical preference for a log transformation

Easier interpretation: multiplicative model

Compare groups using ratios

Interpretation of log predictor and log link for response

Log link used to model the geometric mean of \(Y\)

Exponentiated slope estimates ratio of geometric means across groups

Log transformation of predictor compares groups with a \(k\)-fold difference in there measured predictors

Estimated ratio of geometric means

Interpretation of model

Estimate ratio of geometric mean FEV for two groups differing by \(10\%\) in height (a 1.1 fold difference in height)

To find: Exponentiate \(1.1\) to the slope: \(1.1^{3.12} = 1.35\)

Why transform the predictor?

Typically chosen according to whether the data are likely to follow a straight line relationship

Linearity necessary to predict the values of the parameter in individual groups

Linearity is not necessary to estimate existence of an association

Linearity is not necessary to estimate a first order trend in the parameter across groups having the sampled distribution of the predictor

(Inference about these two questions will tend to be conservative if linearity does not hold)

Rarely do we know which transformation of the predictor provides the best linear fit

As always, there is significant danger in using the data to estimate the best transformation to use

If there is no association of any kind between the response and the predictor, a linear fit (with a zero slope) is correct

Trying to detect a transformation is thus an informal test for an association (multiple testing, which inflates type I error rate)

It is best to choose transformations of the predictor on scientific grounds

In practice, it is often true that mean functions are well approximated by a straight line over a small range of the data

Example: In the FEV dataset, the logarithm of height is approximately linear over the range of heights sampled (look at the plot)

We can often choose untransformed predictors when science would suggest a non-linear association

Can have major advantages in interpreting the results of the analysis

In the FEV example, it is far more natural to compare heights by difference than by ratios

The relative importance of having the “true” transformation for a predictor depends on the statistical role

Predictor of Interest

Effect Modifiers

Confounders

Precision variables

We treat these variables different when planning our analysis

Predictor of Interest (should be pre-specified)

In general, don’t worry about modeling the exact association until you have even established an association (binary search)

Need to have a prespecified model for the POI

Searching for the best fit can inflate the type I error

Make most accurate, precise inference about the presence of the association first

Exploratory models can suggest models for future analyses

Effect Modifiers (difficult to do right anyway)

Modeling of effect modifiers is invariably just a test for the existence of an interaction

We rarely have a lot of precision to answer questions in subgroups of the data

Patterns of interaction can be so complex that it is unlikely that we will really capture the interactions across all subgroups in a single model

Typically, we would restrict future studies to analyses treating subgroups separately

Confounders (matters the most)

It is important to have an appropriate model of the association between the confounder and the response

Failure to accurately model the confounder means that some residual confounding will exist

However, searching for the best model may inflate the type I error for inference about the predictor of interest by overstating the precision of the study

Luckily, we rarely care about inference for the confounder, so we are free to use inefficient means of adjustment (e.g. a stratified analysis)

Precision Variables

When modeling precision variables, it is rarely worth the effort to use the “best” transformation

We usually capture the largest part of the added precision using crude models

We generally do not care about estimating association between the response and the precision variable

8.4 Comments

{{()}}{()}

Point estimates \(\hat{\beta_0}\) and \(\hat{\beta_1}\) were the same for robust and classical standard error

Point estimates \(\hat{\textrm{se}}(\hat{\beta_0})\) and \(\hat{\textrm{se}}(\hat{\beta_1})\) were different for robust and classical standard error

In general, it is hard to predict the effect of using robust standard errors

These were just a a couple of examples and do not constitute a thorough examination of the impact of using robust standard errors

When the model assumptions hold, for these two scenarios, robust standard error estimates were larger than classical standard error estimates

While this is not unexpected, to formally evaluate the amount of increase would require a statistical simulation

Simulate many datasets where the Normality and constant variance assumption holds

For each dataset, estimate \(\hat{\textrm{se}}(\hat{\beta_0})\) and \(\hat{\textrm{se}}(\hat{\beta_1})\)

Summarize the results

Approach will be covered in a future lab